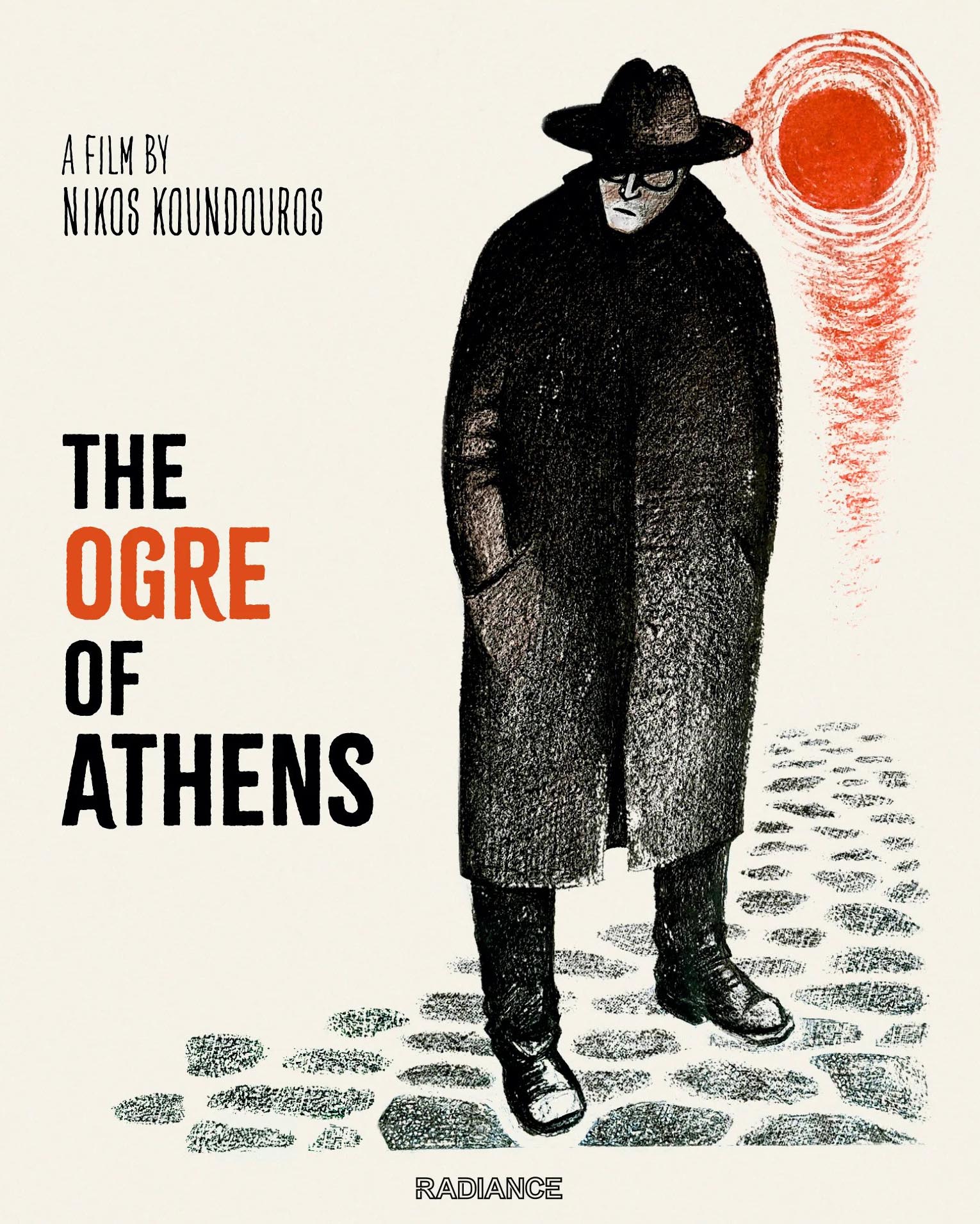

Late in Nikos Koundouros’s The Ogre of Athens, Fatso (Giannis Argyris), the owner of a nightclub that’s a front for a two-bit criminal operation, describes himself as “a cog in the universe.” Seemingly everyone else in the film is also searching for some kind of purpose in life, including Thomas (Dinos Iliopoulos), a nebbish bank clerk who’s too frightened to even buy a new coat because he’s convinced his landlord is going to evict him. When Fatso mistakenly identifies Thomas as his doppelganger, a mysterious underworld crime boss known as the Ogre of Athens, Thomas loses his anonymity and finds his swagger.

Late in Nikos Koundouros’s The Ogre of Athens, Fatso (Giannis Argyris), the owner of a nightclub that’s a front for a two-bit criminal operation, describes himself as “a cog in the universe.” Seemingly everyone else in the film is also searching for some kind of purpose in life, including Thomas (Dinos Iliopoulos), a nebbish bank clerk who’s too frightened to even buy a new coat because he’s convinced his landlord is going to evict him. When Fatso mistakenly identifies Thomas as his doppelganger, a mysterious underworld crime boss known as the Ogre of Athens, Thomas loses his anonymity and finds his swagger.

Made seven years after the end of the Greek Civil War, Koundouros’s film is thick with an atmosphere of moral ambiguity, suspicion, and fear. The Ogre of Athens fittingly embrace the visual language of the film noir to evoke a shadowy world of duplicity and fluid identities, where fantasies of power and freedom run rampant in a populace that has grown to distrust everyone and everything around them.

We see this in Fatso, who’s long been planning a job to steal some ancient columns from the Temple of Olympian Zeus to sell to an eager American buyer. Meanwhile, Thomas, who, finally getting attention from women and a taste of respect from macho men like Fatso and his gang, foolhardily thinks he can permanently commit to his new identity. And there’s also Baby (Margarita Papageorgiou), the young showgirl at Fatso’s club who wants to run off with Thomas to escape her lecherous employer. All three are united by desperation and disillusionment.

Koundouros heightens the film’s sense of unease through the focus on Thomas ingratiating himself to the underworld figures who worship him. Of course, even in his most joyous moments appreciating the perks of his newfound status, Thomas remains blissfully unaware of the noose tightening around his neck. For the way he comes to accept an unearned guilt, he’s akin to a Kafka protagonist, but it isn’t the absurdity of fate that is his undoing. Rather, it’s his insatiable lust for power in a world that has denied him of it at every turn.

The Ogre of Athens is often dizzyingly keyed to the hothouse atmosphere of Fatso’s club. To Thomas’s ultimate chagrin, everyone bows before the altar of unrestrained machismo within the club, as evidenced in the remarkable scene where Fatso and his gang members perform the zeibekiko folk dance, as they do before every job. When Thomas takes part in this show of bravado, it’s abundantly clear that he just can’t fit into the social order. The dance is both a reminder of his delusion of power and, once it’s over, that he really isn’t that different from all the others, as they’re all dazzled by fantasies of freedom that are just that.

Image/Sound

The high-definition digital transfer still bears some signs of damage and slightly blown-out whites in a handful of shots, but black levels are strong in the nighttime scenes and detail is crisp, especially in the many sequences set inside Fatso’s nightclub. Meanwhile, grain distribution is nice and even, nicely retaining the textures of celluloid. On the audio front, the uncompressed mono track is fairly robust, lending a resonance to Manos Hatzidakis’s moody score, while keeping the dialogue forward and clear in the more expansive crowd scenes.

Extras

In a 26-minute interview, the disc’s most substantial extra, Greek film expert Dimitris Papanikolaou situates The Ogre of Athens within the Greek cinema’s golden age and provides essential historical context for its release in the wake of the Greek Civil War. He also discusses the careers of director Nikos Koundouros and several of the film’s actors. In a shorter but no less insightful interview, critic Christina Newland focuses on how Koundouros brings a distinctly Greek post-war worldview to the material, while novelist Jonathan Franzen, in a new introduction, talks about the film’s influence on his book Freedom. The accompanying booklet comes with an extract from Freedom, as well as an essay by director Andréas Giannopoulos that unpacks the threads of identity and national trauma running through the film.

Overall

Nikos Koundouros’s 1956 crime thriller, a classic from the golden age of Greek cinema, remains a potent and relevant portrait of the manly art of self-delusion.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.