The International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam is well known for the way its political engagement and commitment to diversity are reflected in its curation. This curatorial eye felt like a particularly precious gift this year given the concerted vilification of equity and inclusion in certain parts of the world affecting the arts.

One of the highlights of this year’s festival, Claire Simon’s Writing Life – Annie Ernaux Through the Eyes of High School Students, is an ode to one of fascism’s worst enemies: the transformative power of literature. Not just any literature, but what some would refer to as écriture feminine, the kind of writing that’s so visceral and so attuned to the nuances of emotions in deceivingly simple ways that we could never call it masculine.

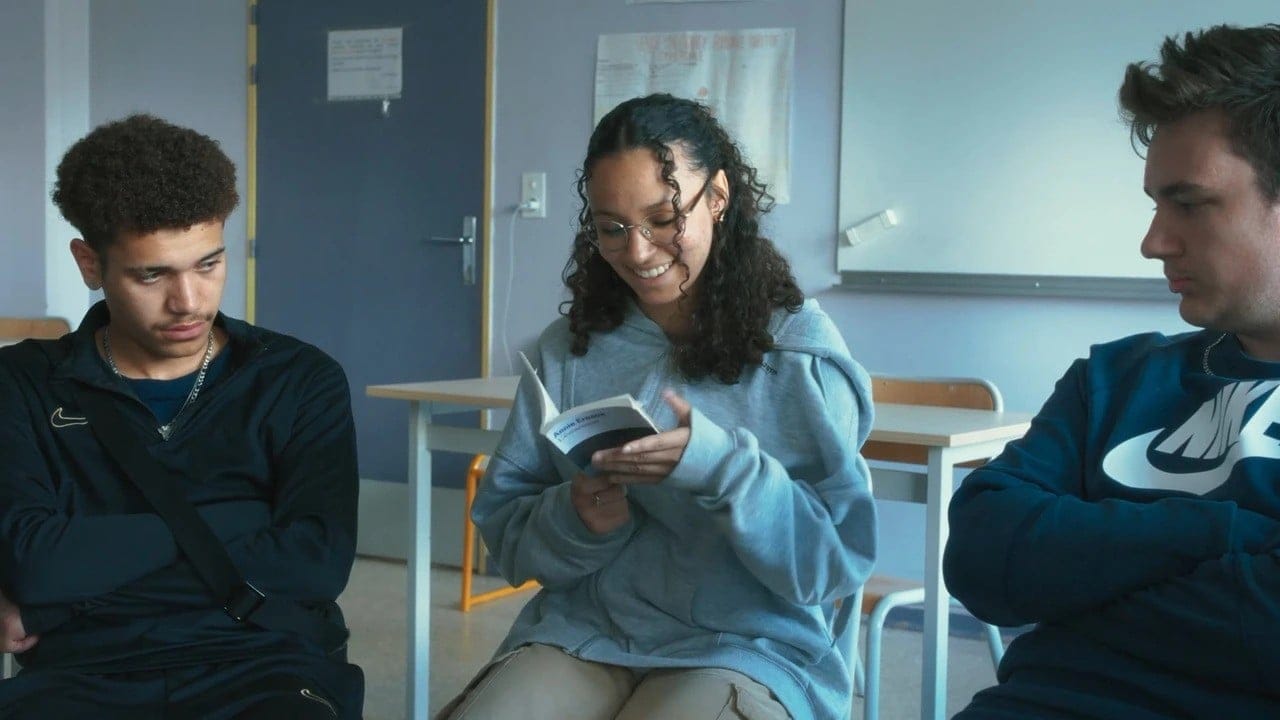

Simon’s film strings together sequences where groups of high school students across various regions of France, including Cayenne in French Guiana, discuss Annie Ernaux’s oeuvre. The film offers the immediate pleasure, one that invites comparison to French cinema of a more fictitious kind, of simply watching people gush over books. Except here these people are young and coming out of their first encounter with this kind of literature, so we don’t witness them perform erudition elegantly—that quintessentially French expertise—but struggle to find the language to articulate the effects that the Nobel laureate’s literature can trigger.

After all, Ernaux’s most striking themes are anything but anodyne: the feminine condition, desire’s violent contradictions, and the alienating experience of being a transfuge de classe, or class defector, someone from a working-class background who manages to climb the social ladder toward a bourgeois environment where they never truly belong.

Only superficially akin to Frederick Wiseman’s work, Writing Life consists almost entirely of classroom discussions, with Simon’s camera fixated on the high schoolers’ newfound passions for the act of reading rather than the functioning of educational institutions. This is a film that shows us that if only the kids read, they’ll be alright—or, at least, better off than the ones who’ve been transformed into zombies by their addiction to screens. In that sense, Writing Life decries our contemporary conditions and announce a possible escape from it.

Something bonds these kids with characters in Ernaux’s books, and to the point that they’re more deeply connected to the world. It’s a life-affirming experience that perhaps only literature can occasion, and perhaps no other film has documented with so little affectation. The students discuss the books and discover new ways of relating to one another that are decidedly at odds with the alienating exigencies of our times. It’s rather refreshing to witness 90 minutes of teenagers speaking to one other and “social media” being mentioned only once, as an aside.

Instead, we’re privy to their creative labor and the pleasures of painstaking argumentation. Equally refreshing are the shots of Ernaux’s books spread out of the on desks, radiant with the promise of deep connections and indelible emotional experiences, as students and teachers browse pages, searching for passages to read aloud. At one point, a girl holds a book up to a boy as if it were an artifact and tells him to read it after he dismisses Ernaux’s writing.

Just as stimulating is how French classrooms don’t shy away from such topics as abortion, sex, and rape. At one point, a young boy reacts to Ernaux’s work by saying that he, too, harbors a family secret that he discovered without his parents being aware of his knowing, and the teacher encourages him to say more instead of changing the subject simply because he hit a nerve. In another pedagogically audacious moment, students discuss a section in Ernaux’s A Girl’s Story where the writer describes the violent experience of losing her virginity to a forceful man who she thinks she loves. At first, they read the section of the book as a rape scene. But with the delicate nudging of the teacher, they start to nuance their immediate response to the violence, realizing that desire complicates everything—especially the notion of consent.

Other highlights of this year’s festival included films that expose precisely what happens when spaces for critical thinking aren’t made available to us. Ulises de la Orden’s The Trial is entirely comprised of archival footage of Argentina’s post-dictatorship courtroom proceedings. We watch as junta leaders, dictator Jorge Rafael Videla among them, are tried for the torture and disappearance of thousands of Argentinians between 1976 and 1983. This is an impeccably edited film where not a single word or image is extraneous. De la Orden’s concision (the three-hour film is culled from over 500 hours of recordings), not unlike Ernaux’s commitment to the deceivingly flat terrain of the factual, renders the atrocities particularly naked before our eyes.

Several sequences in The Trial are stomach-churning, as in one where a victim recalls how a mouse was introduced to her orifices. On the stand, a mother makes a statement about being forced to watch her child get tortured, while another woman describes the moment where she had to decide between being electrocuted or raped. But nothing compares to the testimony of yet another woman who recalls giving birth by herself in the back of a car and how a doctor, upon finally arriving on the scene, tossed the placenta on the ground, then forced the woman to clean up the mess, naked. And it was only then that she was allowed to hold the child.

Morteza Ahmadvand and Firouzeh Khosrovani’s Past Future Continuous, which won the IDFA award for best film in the Envision Competition, is also shaped by the horrors of man. This film about how politics form and de-form human bodies, bringing them together and asphyxiatingly apart, precipitating or delaying the ravages of time isn’t unlike Ernaux’s literary articulations of a woman’s body as pre-conditioned by a continuously oppressive male gaze.

Khosrovani and Ahmadvand, respectively the director and art director of the beautifully auto-ethnographic Radiograph of a Family, recount the predicament of Maryam, an Iranian woman whose exile in the United States is set off by the 1978 revolution. In the narration, Maryam’s voice, as well as that of a man that suggests the embodiment of the parental house itself, reflects upon and mourns a lifetime of separation from her now aging parents.

This melancholy voiceover, delivered in fragments throughout the film, accompanies surveillance images from Maryam’s parents’ home, where cameras have just been set up. The daughter is thus able to follow the parents’ life from afar, watching them engage in everyday activities. The mother does domestic tasks while the father sits nearby with his walker in hand. They dance, or use their phones, but they stop sleeping together after the cameras are installed, as if prudishly aware of their daughter’s perennial gaze—one that metaphorizes the fissures of history, which are quick to re-structure the family in irreparable ways.

Technology allows Maryam to stare at the parents from a vantage point beforehand impossible, but it also makes her disturbingly aware of her impotence, as she’s unable to return to her country out of fear of being arrested upon arrival. The distance between her and her parents makes plain the vileness of the film’s real drama, which remains off camera. All we witness are the effects of its perversity, mediated by a technology with its own perverse promises, as the screens, too, sell closeness but only deliver alienation.

The International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam ran from November 13—23.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.