In Bonjour Tristesse—a modern retelling of Françoise Sagan’s 1954 novella of the same name—the enigmatic fashionista Anne (Chloe Sevigny) discovers a long-held craving just as it’s satisfied by her lover, Raymond (Claes Bang). She describes the feeling as “fizzy,” an adjective that captures the quietly galvanic sensations permeating Durga Chew-Bose’s stringent and striking directorial debut. The interaction also illustrates the inflamed senses of self-awareness that define the film’s characters, who relentlessly observe, analyze, and diagnose each other’s behaviors in ways that invariably reflect back on themselves.

The wealthy, womanizing Raymond enjoys a carefree life in the French Riviera with his stepdaughter, Cécile (Lily McInerny), whose mother died years before. The two have always kept each other company—even solitaire is a multiplayer game for them—and this closeness remains unchallenged when Raymond takes up with the beautiful Elsa (Nailia Harzoune), whose warmth grounds the brainy and impulsive pair without undermining their thick-as-thieves rapport.

Elsa is sensitive to the 18-year-old’s burgeoning womanhood in ways that her father isn’t. They watch Cécile tiptoe along a rocky beach in an early scene, and Elsa remarks, “She’s imagining what she looks like to us,” and suggests that she’s practicing for when she wants to be seen. Raymond, tellingly, bemoans the idea of his daughter being ogled by local boys, but Elsa stresses her wording: “I said seen, not looked at.” Her words evoke a strain of self-perception that’s negotiated through the eyes of others—one that, for better or worse, is a staple of adolescence.

Though Bonjour Tristesse’s young protagonist demonstrates the wit and bearing of a woman beyond her years, precocity can often be hard to distinguish from mimicry. Cécile is unmistakably a teenager, and Chew-Bose, in tandem with the nimble McIrney, goes to commendable lengths to flesh out this clever and impulsive girl’s deeper immaturities.

As Raymond will discover, Cécile is already an object of desire for Cyril (Aliocha Schneider), their handsome neighbor. They steal away to revel in sensual summertime languor—exploring the scenery and, of course, each other—but this idyllic vacation is quickly derailed by Anne’s arrival from Paris. Cécile gravitates toward this old friend of Raymond and her mother’s, but the two women’s shared affinity runs counter to Anne’s competitive dynamic with Elsa. It doesn’t take long for Raymond’s affections to shift, which sets his confused, resentful daughter against the well-meaning Anne. As her matriarchal care and attention start to conflict with Cécile’s desires, the young woman gradually—and, in the end, disastrously—discovers her mean streak.

Chew-Bose’s background as a culture writer is evident in her script’s intellectual flourishes, which charge the film’s quotidian interactions with a fine-grained psychology. The characters seem to relish their words, savoring the thrill of a pithy remark or canny assessment, and that pleasure, for the most part, is shared with the audience. In an interview for Reverse Shot, the director implies a personal proximity to her characters, and this evident mixture of affection and understanding vivifies exchanges that could have come across as stiff or expository.

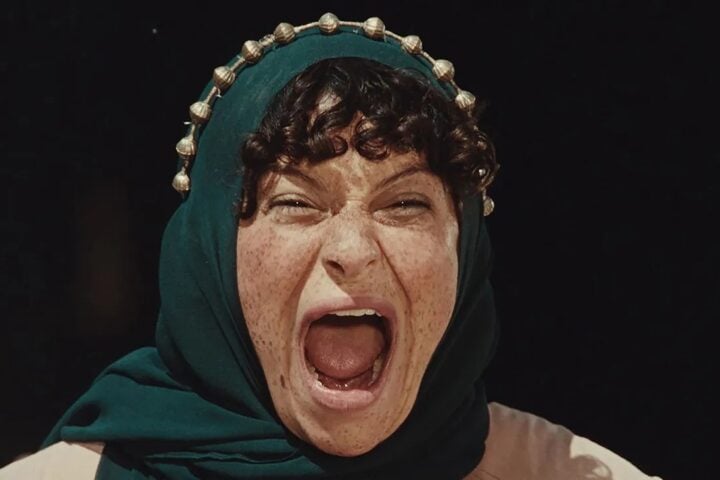

Chew-Bose also animates her sharp dramaturgy with a rigorous, tactile aesthetic; her curious yet patient camera pays close attention to the sun-dappled textures of cloth, skin, and jewelry as figures slink and lounge their way through Bonjour Tristesse’s dynamic, indelible frames. Even when she shoots her subjects in close-up, the compositions feel spacious.

Remarkably, Bonjour Tristesse’s expertly curated, if at times rigid, vibes are never punctured by the constant presence of cellphones and their related technologies. If anything, the gadgets are a core feature of the film’s ennui (in a pivotal moment of distress, Cécile tries in vain to untangle her headphones). This attention to the fixtures of the modern world lends a timeless story a newfangled tenor, one that’s carried forward by an original epilogue that lingers on the precipice of change, finding a state of grace in that torrential pull between the familiar and the new.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

Astonishing that a review about a re-make of the coveted Otto Preminger film from 1957 never mentions it.