As a filmmaker, Jem Cohen thrives on ambiguity, dissolving the lines between documentary and fiction until the two become nearly indistinguishable. Little, Big, and Far is no exception. Ostensibly a quiet portrait of astronomers reflecting on their work and the changing world around them, the film initially presents itself as an observational documentary. But that façade slowly erodes, revealing a heavily constructed narrative—one subtly but unmistakably shaped by the experimentally inclined hand of its maker.

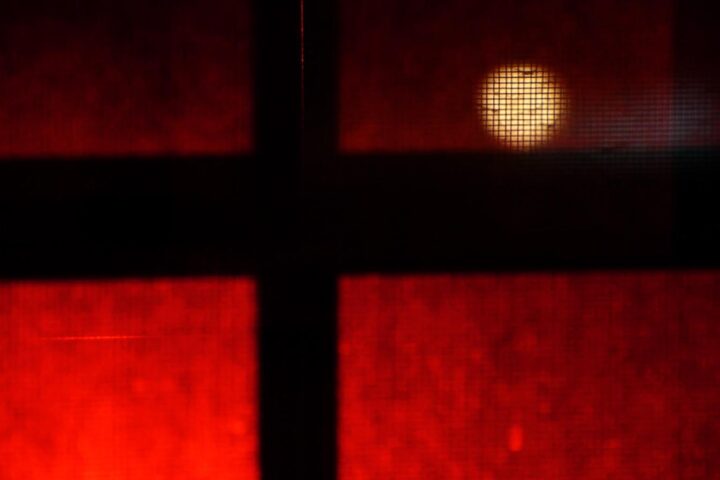

At the center of the film is Karl (Franz Schwartz), a 70-year-old Austrian astronomer, professor, and museum consultant whose days are filled with cosmic contemplation. Early on, he shares his love for jazz—music that he likes to play while poring over celestial images. The film is also focused on Sarah (Jessica Sarah Rinland), a younger colleague preoccupied with the Anthropocene, and Karl’s wife, a cosmologist named Eleanor (Leslie Thornton), who communicates with her husband via epistolary methods from Texas. Across a tapestry of images—museums, weathered buildings, industrial ruins, and visualizations of deep space—that gradually form a kind of thematic collage, we learn about their lives and fixations.

Yet for all its structural density and artful montage, Little, Big, and Far struggles to compellingly link its central ideas. Midway through the film, Karl decides to linger in Greece after a conference, hoping to find a patch of sky dark enough to truly see the stars. It’s a moment that gestures toward a larger point: that the universe’s vastness is drowned out by the noise of modern life. But Little, Big, and Far’s execution renders this epiphany strangely anemic.

The film adopts a diaristic, epistolary form that flattens its emotional topography. The more the characters narrate their thoughts, the more Little, Big, and Far comes to feel distant and airless, despite its intimacy of subject. Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s Homo Sapiens, from 2016, similarly fixates on the ephemerality of civilization with far greater economy, but it does so without the utterance of a single word, or even showing us a single person. That film’s haunting succession of crumbling buildings and abandoned structures speak volumes, evoking humanity’s impermanence with a stark, unflinching clarity that Little, Big, and Far only gestures toward.

Cohen’s central conceit—the mimicry of documentary form within a fictional framework—is, in theory, a smart one. It challenges the illusion of objectivity in nonfiction cinema, a reminder that even the most observational films are guided by selective framing and editorial intent. But here, that experiment lands with more friction than insight. Where The Blair Witch Project used nearly this same tactic to thrilling, disorienting effect more than 25 years ago, Little, Big, and Far applies it to little dramatic or intellectual payoff. The ambiguity of whether what we’re watching is rooted in reality or scripted doesn’t enrich the viewing experience.

While Little, Big, and Far’s characters muse on humility and the vastness of existence, Cohen positions himself as a kind of omniscient puppeteer, playing god in a film ostensibly about surrendering to forces larger than ourselves. The result is an aesthetically austere, formally adventurous hybrid work that ultimately feels claustrophobic—so wrapped up in its own conceptual rigor that it leaves little space for discovery, or wonder.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.