“As for wanting to find in all that a broader, loftier meaning to carry away from the performance, along with the program,” Samuel Beckett wrote of his 1952 play Waiting for Godot, “I cannot see the point of it.” The challenge, then, for any director approaching Beckett’s landmark work—in which two woebegone men pass the time while waiting for the arrival of a man they’ve never met—is to release us from the expectation that they must locate that “broader, loftier meaning” somewhere in this densely delirious script.

Jamie Lloyd’s revival of Waiting for Godot, starring Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, effectively does just that, framing the play less as linear drama than as something more akin to a multi-movement piece of instrumental music. Though Lloyd has become recently synonymous (through viral clips of his revivals of Sunset Boulevard and Evita) with tracking actors outside the theater with handheld cameras and dousing his shirtless leading men in paint, his best work has been his most genuinely minimalist productions of Cyrano de Bergerac and A Doll’s House. Those stagings pared the plays down to their most essential element: language.

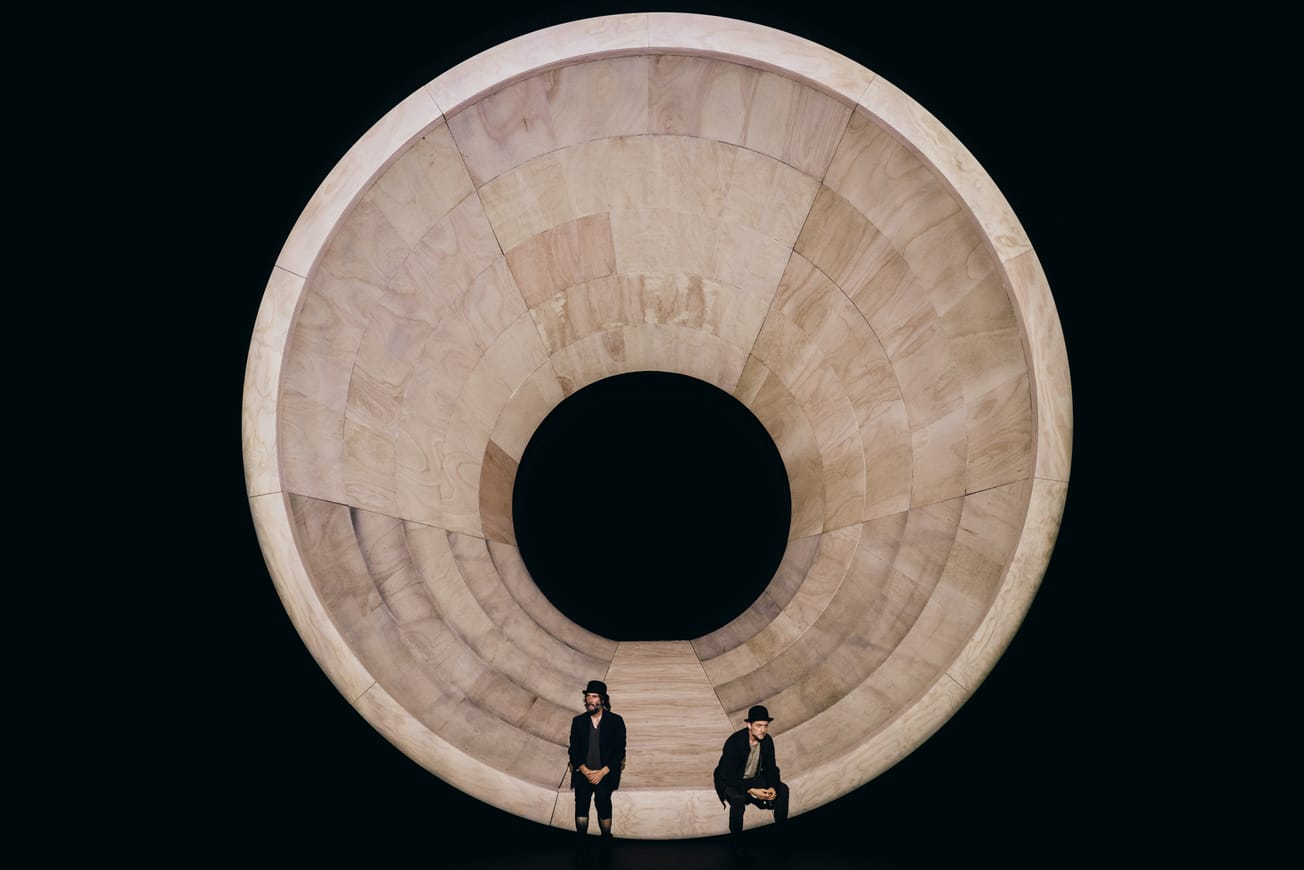

That’s the right approach to Beckett—facing the oft-impenetrable text head-on—and Lloyd eliminates almost of his past auterish distractions. Characters actually speak directly to each other rather than out to the audience as they do in many Lloyd productions, and the claustrophobic set—Soutra Gilmour’s interior of a white marble-wood cylinder looks like it could be the inside of an eye—remains stationary (the turntables in his Betrayal and A Doll’s House went around and around). He even tones down his ASMR approach to micing actors, save for a brief playfully echoey sequence in the second act (Ben and Max Ringham provide the sound design). If this Waiting for Godot seems strange and avant-garde, you’ll have to blame Beckett.

In Lloyd’s hands, with minimal movement and maximal attention to language, Waiting for Godot becomes all about Beckett’s rhythms, with the meaning of each line secondary to the repeating patterns of words and phrases and actions. This is Beckett as jazz. Or it would be if Lloyd’s stars consistently played, so to speak, in tune.

Bill & Ted buddies Reeves and Winter have a tender rapport, but they often seem more like one two-headed being than clearly differentiated characters. Reeves’s Estragon is amusingly wearier in his delivery than Winter’s Vladimir, but it’s difficult to pinpoint any more significant contrast between them. Winter tends toward a sort of stilted, presentational tone, offering a verbal sameness throughout that seems to work against Lloyd’s emphasis on the text’s diverse tempos.

Reeves might make more of an emotionally flexible Estragon opposite a more pliable partner. And though he and Winter do a lot of sliding exhaustedly down the cylinder’s curved walls, neither actor’s physical comedy is quite crisp enough. But perhaps the relative chill of the Vladimir and Estragon scenes lays down a groove for the scene-stealing sequences featuring Pozzo (Brandon J. Dirden) and his slave Lucky (Michael Patrick Thornton), the mirroring duo who show up in each act. Dirden and Thornton sizzle where Reeves and Winter gently boil.

Dirden, terrific here as he was most recently in Take Me Out and Skeleton Crew, offers a sleazy, serpentine Pozzo. He’s grossly abusive to Lucky, belching commands at him and cracking an invisible whip (all the props are, sometimes confusingly, mimed) on his back. He’s cruelly magnetic, an explosively riffing saxophone cadenza of a performance.

And Thornton, proving as he did in A Doll’s House to be a reliable collaborator for Lloyd on the director’s quest to make language the focal point of his productions, is a winkingly expressive Lucky. In one of Beckett’s least lucid passages, Lucky, who here is muzzled when Pozzo first brings him on stage, receives a bowler hat to aid in his thinking and then delivers a monologue of free-associative intellectual thought to an impressed Vladimir and Estragon. Thornton wields the words as a virtuosic drum solo, ending on a whisper like a fading hi-hat cymbal. Instrumentals may not have legible literal meanings—nor do Beckett monologues like these—but they do have emotional valances, and Thornton expertly navigates the poetry’s heated arcs.

Thornton is a wheelchair user and Lloyd wants us to see Lucky as a character with a disability. When Pozzo shouts, “He can walk!,” after Lucky collapses post-monologue, Thornton turns to the audience and wryly shakes his head. But it’s not always apparent what Lloyd wants us to make of a disabled actor playing a character who’s abused and enslaved: Lucky’s disability amplifies Pozzo’s monstrousness but also implicates Estragon, whose demands that Lucky dance for him, and subsequent attack on Lucky’s performance, take on a more vicious tone.

But tracing Estragon’s character development—or anyone’s—isn’t the point of a play that constantly provides its protagonists a chance for renewal should they choose to take it. By the time everyone reunites for a second night in act two, only Vladimir remembers the previous evening’s exchanges. Vladimir and Estragon fail to renew themselves, of course, falling over and over again into the same patterns of speech, of movement, of inertia.

“We are bored to death, there’s no denying it,” Vladimir reminds Estragon. “A diversion comes along and what do we do? We let it go to waste.” If there’s a deeper meaning bleeding out from Lloyd’s revival, perhaps it’s this production’s exploration of how desperately we try to grapple with the passing of time, toiling to turn each ephemeral moment into a scene worth playing.

Waiting for Godot is now running at the Hudson Theatre.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.