Pushing the tropes of the Heroic Bloodshed genre that he codified a few years earlier, John Woo’s 1989 classic The Killer lays out the heightened emotions of its pistol opera in its opening seconds. As a hitman, Ah Jong (Chow Yun-fat), receives his latest assignment in a church, the cold exchange of money and equipment is juxtaposed with the sights of a looming crucifix and fluttering doves and the sound of a woman singing a Cantopop torch song. The singer, Jennie (Sally Yeh), is performing in the bar where Ah Jong’s target is relaxing, and she finds herself caught in the crossfire when the hitman arrives, ultimately blinded by the muzzle flash of his pistol.

Pushing the tropes of the Heroic Bloodshed genre that he codified a few years earlier, John Woo’s 1989 classic The Killer lays out the heightened emotions of its pistol opera in its opening seconds. As a hitman, Ah Jong (Chow Yun-fat), receives his latest assignment in a church, the cold exchange of money and equipment is juxtaposed with the sights of a looming crucifix and fluttering doves and the sound of a woman singing a Cantopop torch song. The singer, Jennie (Sally Yeh), is performing in the bar where Ah Jong’s target is relaxing, and she finds herself caught in the crossfire when the hitman arrives, ultimately blinded by the muzzle flash of his pistol.

Wracked with guilt over maiming the woman, Ah Jong attempts to use one last job to raise the money for her needed cornea transplants, only to end up double-crossed by his friend and manager, Fung Sei (Chu Kong), who’s tormented by being strong-armed into this treachery by triad boss Wong Hoi (Shing Fui-on). Making the assassin’s life even more difficult is the pursuit of loose-cannon cop Li Ying (Danny Lee), who begins to struggle between his reflexive desire to put a few rounds into the killer and the observations he makes about Ah Jong’s sense of honor and protectiveness toward civilians like Jennie and a small girl wounded by gangsters.

Woo establishes all of this within the first 20 minutes of the film. Re-teaming with A Better Tomorrow editor David Wu, Woo cuts the film according to an intuitive, emotional logic that leans even more heavily into long dissolves between shots and superimpositions than their previous collaboration, dragging out the slightest movement for several beats. In an early assassination, for example, the simple act of Ah Jong pulling out and aiming a rifle isn’t only captured in slow motion but replayed twice in quick succession, transforming what could have been a perfunctory shot into something almost dreamlike and suspended in time.

The florid aesthetics naturally inform the action sequences, which are all dazzling bullet ballets of Ah Jong—and, eventually, Li—duking it out with gangsters in locales ranging from bay shores to the church from the opening scene where bad guys keep appearing seemingly out of nowhere. Logic takes a backseat here to the grotesque beauty of it all as a career killer and a brutish cop work toward some kind of divine atonement through the very violence that damns them.

Despite the relentless onslaught of show-stopping action sequences, The Killer never loses sight of the personal relationships and existential angst that it sets up in the first act. The slow thaw of mistrust between Ah Jong and Li, as well as the fraternal care both men exhibit toward Jennie, are captured in small gestures of comfort between the characters and terse, noirish phrases that hint at the men’s growing discontent with their professions. Weighing a Beretta in his hand as he prepares for yet another battle with gangsters, Ah Jong mutters to himself, “It’s easy to pick up but hard to put down,” hinting at a desire to save more than just his skin.

While Bullet to the Head would take Woo’s emotional stakes to higher, more explicitly political levels and Hard Boiled would push his action choreography to its most grandiose extreme, The Killer remains his finest balance of ballistic genre filmmaking and underlying humanism. Capped off by the most heart-wrenching finale of the director’s career, the film tests the limits of Woo’s belief in redemption, finding it in only the most abstract sense even as every facet of a typical happy ending is brutally withheld from the characters.

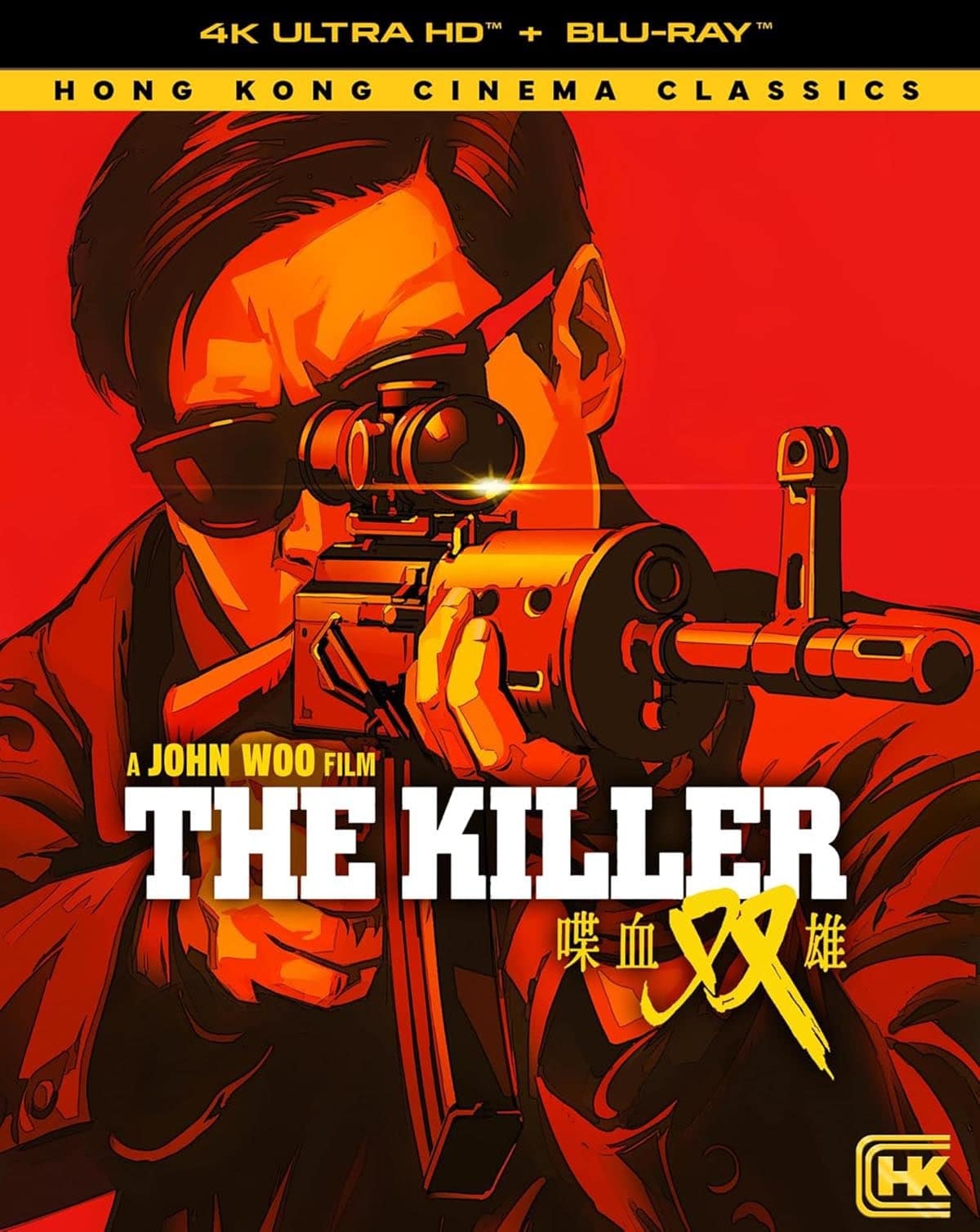

Image/Sound

Shout!’s 4K transfer looks accurate to the strengths and weakness of 1980s Hong Kong cinema. Brightly lit scenes tend to have a soft, gauzy quality, while a thick layer of grain coats the darker scenes. Nonetheless, detail and balance are consistent throughout, with good color separation and accurate flesh tones. The Cantonese mono track inherently lacks depth, but the film’s copious explosions and swells of romantic music are well-distributed around the centered, post-synchronized dialogue, and nowhere do the sounds become muddied or congested.

Extras

The disc housing the film comes with three commentaries, starting with an archival track that John Woo and producer Terence Chang contributed to the Criterion laserdisc not long after The Killer’s original release. They explain how they made the film and how Woo approached the project as a tribute to filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Jean-Pierre Melville.

In a newly recorded track, Woo sounds wistful in the way he constantly drops anecdotes, though he does occasionally offer the choice bit of analysis, as when he brings up the early, iconic shot of Chow Yun-fat in front of a bloody background and says that it was inspired by the blood-spewing elevator from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Another new commentary features critic David West, who unpacks the film’s heavy symbolism and its core relationship bond being not that of Ah Jong and Jennie but of the hitman and Li.

The feature-length “The Hero of Heroic Bloodshed” leads off a bonus disc packed with new extras. The documentary includes interviews with collaborators, critics, and admiring filmmakers like Roel Reiné, who all extol Woo’s influence on Hong Kong and action cinema as a whole. A separate interview with Woo lasts for 45 minutes and extensively covers the convoluted path of The Killer’s making and how the benefit of hindsight has allowed the filmmaker to see how the film’s themes of forgiveness helped him process his own feelings of resentment toward Tsui Hark for the difficulties that Woo faced getting projects approved in the late ’80s.

Also included are interviews with editor David Wu, who fascinatingly discusses how he cut the film around musical cues and emotional beats, and producer Terence Chang. Elsewhere, author Grady Hendrix contributes an in-depth discussion of how the film revolutionized Hong Kong cinema’s approach to police and crime. Finally, the disc is rounded out by some deleted and extended scenes, and the accompanying booklet contains critical essays on the film and its legacy by Hendrix, Victor Fan, Calum Waddell, and Brandon Bentley.

Overall

Right issues have kept John Woo’s masterpiece out of print in America for years, but at long last it returns in a definitive release with a projection-accurate transfer and a wealth of extras.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.