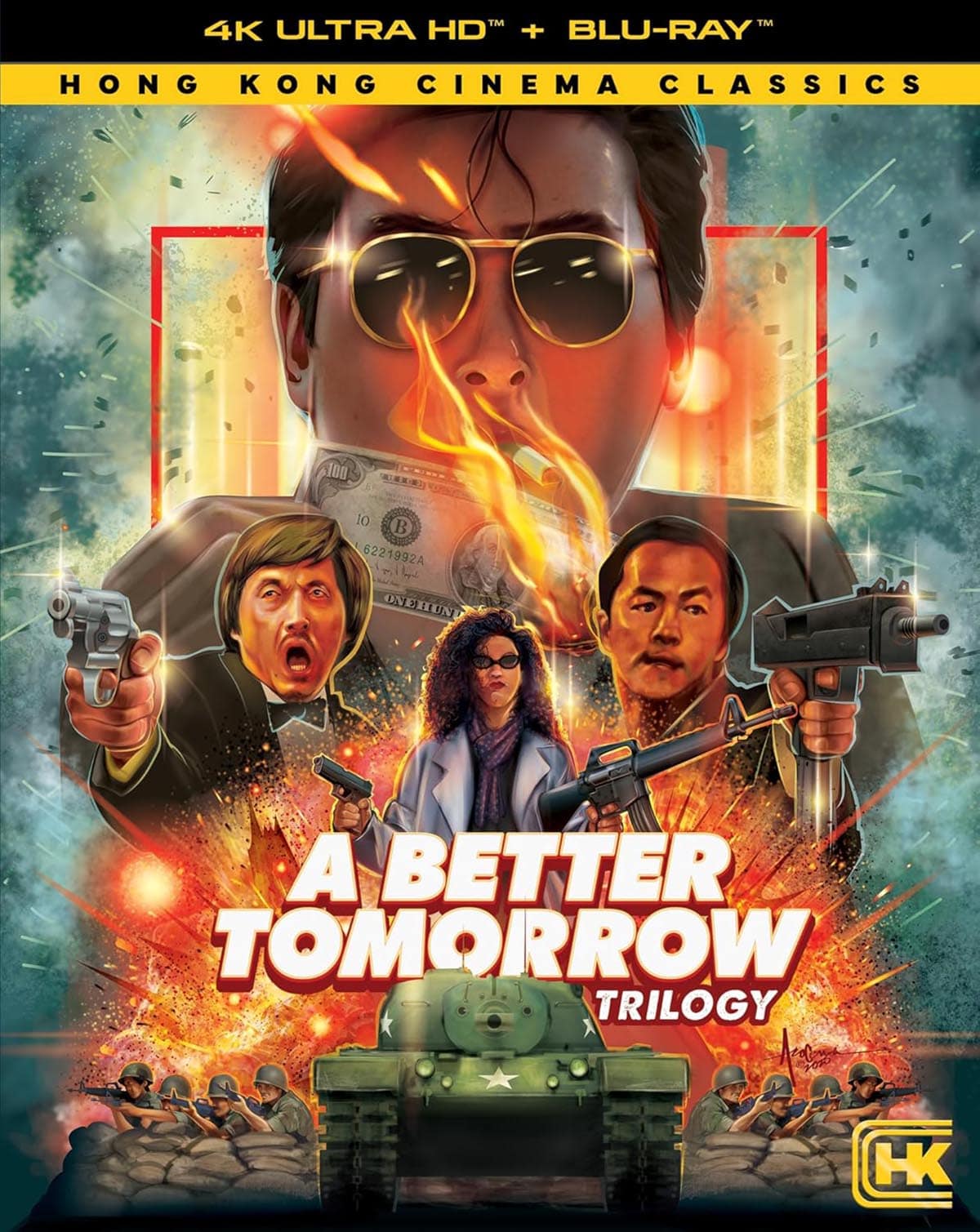

John Woo was something of a journeyman for the first 15 years of his career, moving from an assistant director role at Shaw Bros. to work-for-hire wuxia and comedy projects at Golden Harvest with a spotty record of box office success. As such, when he hit upon an idea to make a modern action melodrama inspired by the 1967’s The Story of a Discharged Prisoner and took it to Cinema City Enterprises, he had to lobby hard for the assignment, only snagging it thanks to support from one of the studio’s top filmmakers, Tsui Hark. Out of step with prevailing audience tastes for comedy, A Better Tomorrow opened in theaters in 1986 with the expectation that it would lose money. Instead, it proved to be the single most paradigm-shifting action film in Hong Kong cinema since The One-Armed Swordsman.

John Woo was something of a journeyman for the first 15 years of his career, moving from an assistant director role at Shaw Bros. to work-for-hire wuxia and comedy projects at Golden Harvest with a spotty record of box office success. As such, when he hit upon an idea to make a modern action melodrama inspired by the 1967’s The Story of a Discharged Prisoner and took it to Cinema City Enterprises, he had to lobby hard for the assignment, only snagging it thanks to support from one of the studio’s top filmmakers, Tsui Hark. Out of step with prevailing audience tastes for comedy, A Better Tomorrow opened in theaters in 1986 with the expectation that it would lose money. Instead, it proved to be the single most paradigm-shifting action film in Hong Kong cinema since The One-Armed Swordsman.

An opera of sorts whose elaborate gunfights are its arias, A Better Tomorrow hinges on the attempts of a successful senior-ranking triad counterfeiter, Ho (Ti Lung), attempting to go straight after serving time thanks to a setup by a former underling, Shing (Waise Lee). Complicating matters are Ho’s frayed relationships with friend and fellow gangster Mark (Chow Yun-fat), who urges Ho to pursue revenge against Shing no matter the cost, and Ho’s brother, Kit (Leslie Cheung), a police officer who blames his sibling for the murder of their father. With Shing eager to tie up loose ends and Mark willing to fight whether Ho wants to or not, things rapidly escalate into the sort of violence that our protagonist hoped to never see again.

By now, “John Woo” has become as much an adjective as a proper noun, an immediate signifier of a certain approach to action defined by elaborate, balletic movement and heavy use of slow motion. Woo planted the seeds of that style in A Better Tomorrow. In an early scene, Mark deals with some rival gangsters in a restaurant by bursting into their private room dual-wielding Beretta 92F pistols before retreating back into a corridor where he’s planted additional guns in flower pots to save him the time and risk of reloading. In the climax, Ho, Kit, and Mark must face down Shing and a small army of triad enforcers at a commercial pier filled with barrels whose flammable liquid is ignited by stray gunshots into explosions and roaring fires.

Woo matches such outsized set pieces with character beats that are played for similarly maximal sentimentality, but A Better Tomorrow is most resonant in its quieter moments. Early on, Mark’s bravado slips in a scene where he alludes to the abuse he suffered at the hands of superiors when he first entered the mafia. Elsewhere, scenes depicting the fraternal tension between Ho and Kit subtly draw on a metatextual layer of the generation gap between Lung, a major star of wuxia cinema in the 1970s now entering middle age, and Cheung, one of the luminaries of the emerging wave of ’80s idols. (At times, the actors’ interactions even recall those of John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Howard Hawks’s Red River.)

A Better Tomorrow’s runaway success all but guaranteed a sequel, which was released in 1987. Two years after the events of the first film, Ho is called in by police to assist Kit with taking down another of Ho’s old associates, Lung Sei (Dean Shek). A Better Tomorrow may have been about two brothers on either side of the law, but it’s true star was Mark, whose hyper-cool charisma propelled Chow to international stardom. With Mark going out in a blaze of glory at the end of the first film, Woo and Tsui had to find some way to bring the actor back. Befitting the soapy essence of the series, they introduced Ken, an identical twin unknown even to Mark’s friends, and whom Ho and Kit meet while tracking Lung down in New York City’s Chinatown.

To complicate matters, Woo and Tsui fell out behind the scenes over creative differences. Where Woo wanted to maintain the focus on Ho and Kit’s relationship, Tsui saw Lung as the story’s protagonist. It’s easy to see Tsui’s perspective: While Ho and Kit have largely repaired their bond and lack the same compelling conflict that drove the first film, Lung is vastly more interesting as a man whose own attempts to leave the mafia result in the mind-shattering trauma of witnessing his young daughter murdered in front of him. Lung’s subsequent drift in and out of catatonic madness is the only emotional through line of A Better Tomorrow II.

Woo and Tsui each ended up sneaking into the editing booth to keep recutting the film closer to both of their respective visions, leading to a final edit that transitions haphazardly between plotlines that are simultaneously overstuffed and underdeveloped. Only a few minutes longer than the first film, A Better Tomorrow II feels distended and unfocused. Still, the action scenes are stellar enough to warrant multiple viewings. Best of all is the final firefight, a bloody rampage through a mansion that clearly taught Woo a thing or two about mounting complex choreography across multiple sets that he would expand further with Hard Boiled.

Though Woo had already written a treatment for a third film set before the events of A Better Tomorrow during the Vietnam War, he left the franchise following the release of the second film, leaving Tsui to rework Woo’s general concept ahead of A Better Tomorrow III: Love and Death in Saigon going into production. Released in 1989, the film sees Chow returning to the role of Mark, who travels to Saigon during the war to help his cousin, Michael (Tony Leung Ka-fai), and uncle (Shih Kien) get out of the country and back to Hong Kong. As they must, things quickly go south, with the uncle dying amid one of many explosions of violence and the cousins finding themselves aligned with an arms smuggler, Chow Ying-kit (Anita Mui), who navigates the various internal and external paramilitary forces tearing apart Vietnam.

On the surface, A Better Tomorrow III swaps out the interest in fraternal bonds that defined the first two movies with a romantic entanglement. Both Mark and Michael develop feelings for Kit, who in turn expresses interest in Mark, who then backs off for the sake of not hurting his cousin. Replacing the bristling tension of relationships with a conflict rooted in the characters’ mutual care and desire to placate the others brings a new dramatic angle to the franchise.

This softer side is even more interesting when set against the film’s political subtext. A Better Tomorrow III jettisons Woo’s perspective on the heroism of “necessary” violence for an unsparing portrayal of the labyrinthine conflicts that rent Vietnam apart in the 1960s and ’70s. Not merely depicting a war between North and South or even the Vietnamese and the West, the film shows regions descending into warlordism and where paranoia reigns. The filmmakers never hides their sense of disgust at the imperial predations upon the country, which in turn saps the action of the hedonistic thrill that marked the other movies in the series.

Tsui’s action direction bears some similarities to Woo’s, chiefly in the extensive use of slow motion and some complex camera movements, but the filmmaker puts his own stamp on the sequences with a grittier, more grounded approach. Tilted angles convey the disorienting sensory overload of a firefight, and the slow-mo tends to draw out not so much the badass imagery of brandishing a gun and squeezing the trigger so much as the fatal aftermath.

While Woo wrings operatic tragedy from death, Tsui focuses on the blunt finality of it, of seeing an erstwhile cocky wannabe hero cradling the limp body of a loved one with a look of wild panic and anguish. Though a major tonal diversion from what preceded it, A Better Tomorrow III ends the franchise on a reflective note that retroactively colors the movies whose narratives occur after this one. Suddenly, the title of the trilogy takes on a sickly ironic tone, closing the loop on a cycle of destruction that will eventually claim all its major players.

Image/Sound

Shout! Factory’s set presents new 4K restorations of the films, and they’re aided and abetted by Dolby Vision. These aren’t the most visually pristine movies—some of the nighttime scenes suffer from a loss of definition from having been shot in low light—but there are no compression artifacts or any other issues traceable to poor video encoding. Detail is fine enough for the viewer to make out the smallest pieces of debris scattered by explosions or the subtle gradations of white and yellow in muzzle flashes, and the naturalistic color palettes are faithfully rendered.

All three films in the series come with their original Cantonese mono tracks, all of which are clear, if a bit unavoidably lacking in depth. Dialogue sits at the front of the mixes and is never swallowed by the reverberating sounds of gunfire and explosions.

Extras

The first two films come with a commentary by critic James Mudge, while the third comes with a track by critic David West. All three tracks are heavily focused on the Hong Kong cinema of the time, the films’ formal innovations, and John Woo and Tsui Hark’s competing visions.

Each film is also supplemented with new interviews with various crew members, critics, and, in the case of Better Tomorrow III, a Vietnam War researcher, Dr. Aurélie Basha i Novosejt. The latter is a particularly fascinating interviewee for attesting to the subtle complexity of the third film’s attention to historical detail amid all of the epic action.

Especially of note is Woo’s reflections on the boost his career received from the original film, and he gets candid about the difficulty making the sequel. Given how passionately he fought with Tsui during shooting and post-production, it comes as a surprise when Woo admits he never wanted to make a sequel to the original film in the first place, agreeing to make it only to prevent producers from handing it off to someone else and potentially cheapening the material.

The only glaring omission here is any sort of perspective on the films from Tsui, and considering just how thorough this release is, one is left with the impression of deliberate abstention on his part. A bonus 2K Blu-ray includes an alternate cut of A Better Tomorrow II containing around a half-hour of deleted scenes, as well as a version of the third film edited for release in Taiwan.

Overall

Shout! Factory’s lavish box set brings the long out-of-print films back into domestic circulation with phenomenal new transfers and a host of informative extras.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.