Nicholas Hytner’s The Choral follows a choral society in the fictional English town of Ramsden at the height of World War I as it prepares for its next performance. With the choir master and many of the choir’s members having been lost to the war, the locals turn to the talented but controversial Dr. Henry Guthrie (Ralph Fiennes).

Guthrie, an organist turned conductor, has returned to the U.K. after working in Germany for many years, which is enough to draw the ire of many. His fondness for German composers doesn’t do him any favors, but his belief that art should transcend barriers of personal identity and speak to the deepest parts of the human soul proves inspiring. By that lofty measure, The Choral is a failure, a historical drama with a handsome enough period setting and a couple of pleasant musical moments but whose roteness keeps it from resonating.

The film features a sprawling cast of characters that runs the gamut from the bigwigs in charge of the choral society, like the dour Alderman Duxbury (Roger Allam) and his jovial sidekick Mr. Fytton (Mark Addy), to lads like Lofty (Oliver Briscombe) and Ellis (Taylor Uttley) who are still just too young to be drafted into the war, so they get drafted into the choir instead. It’s a Middlemarch-esque approach to painting life in a small English town, with each of the many characters, from Salvation Army nurse Mary (Amara Okereke) to neighborhood sex worker Mrs. Bishop (Lyndsey Marhsall), providing one stroke on a vast canvas.

But the result is that all of the individual characters—youngsters, war widows, elders, baker’s apprentices, and more—are left underdeveloped and emotionally unengaging. And though the film, as written by acclaimed English playwright Alan Bennett, works rather frantically to pair them all off, their relationships and romances are similarly shallow.

The Choral sets out to mix comedy with tragedy, but it’s an unsuccessful brew. The jokes come thick and fast, and while there are a few good lines, the hit rate isn’t very high. In the film’s most strenuous attempt at tear-jerking, a wounded soldier named Clyde (Jacob Dudman) suddenly interrupts one of the choir’s rehearsals with a monologue about the horrors of the battlefield that’s so unprompted and so excessively theatrical that it’s more bizarre than devastating.

The Choral’s tonal struggles are at their most pronounced whenever the subject of sex comes up. The film begins with a somber sequence in which Lofty delivers telegrams to women whose husbands have been killed in action, only for Ellis to immediately begin making leery jokes about his chances of sleeping with them. Later on, we watch Clyde guilt an unwilling woman into touching him in a grim scene that the movie makes no attempt to reckon with afterward.

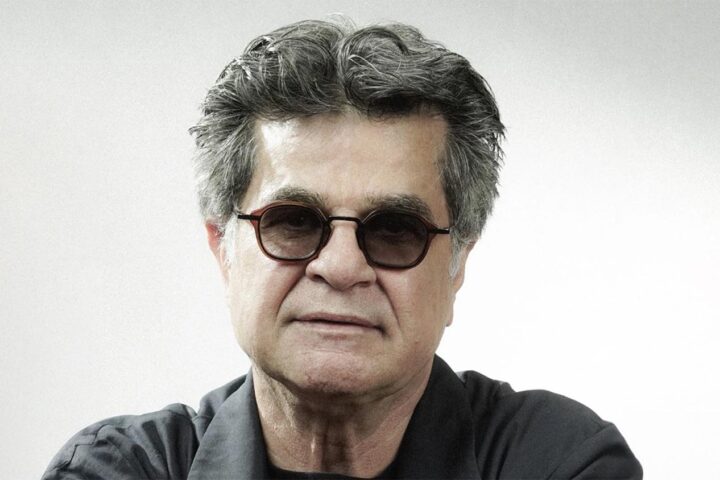

At the center of it all is Fiennes, who, like Guthrie, works bravely to make something out of the material he’s been given. Of course the man who can bring gravitas to a TikTok trend keeps the film from completely falling apart, and a scene in which he counsels Clyde is moving. But his character is still underwritten, and by the end we have no greater sense of what makes Guthrie so brilliant or what makes him tick than we did at the beginning.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.