In an age where cinema must contend with the growing threat of authoritarianism, few artists point toward the light of free expression quite like Jafar Panahi. Despite facing a filmmaking ban of 20 years in Iran, the dissident director consistently found a way to make features that he smuggled out of his native country. Following Panahi’s 2022 stint in prison, Iran’s theocratic regime has finally lifted its ban on him making films.

The filmmaker nonetheless opted to make his latest feature, It Was Just an Accident, outside of official channels to avoid submitting scripts for official approval. His first post-ban film provides a sobering portrait of the choices that everyday Iranians are forced to make because of the regime’s repressive policies. Panahi draws from memories of his recent stint in prison for a fictional tale set among characters all grappling with the meaning of their own time behind bars.

Car mechanic Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri) kickstarts the story’s chain of events when he becomes convinced that he’s encountered his former prison interrogator, Eghbal (Ebrahim Azizi). He moves quickly to round up some fellow former prisoners, each of whom is in varying stages of reintegration into everyday life. Yet even after Vahid apprehends their suspected tormentor, their only certainty lies in the pains of their own experiences inside the jailhouse.

What Vahid and his conspirators assume will be the end of the road is revealed to be an intersection with no clear direction forward. They struggle to confirm beyond a shadow of a doubt that Eghbal was the interrogator, given that, as blindfolded prisoners, they only heard him. The group finds even less alignment as to what, if any, consequences their hostage should face. More than a snapshot of contemporary Iranian society, It Was Just an Accident is a roadmap toward the fraught moral questions that Iran will have to face after its regime ends.

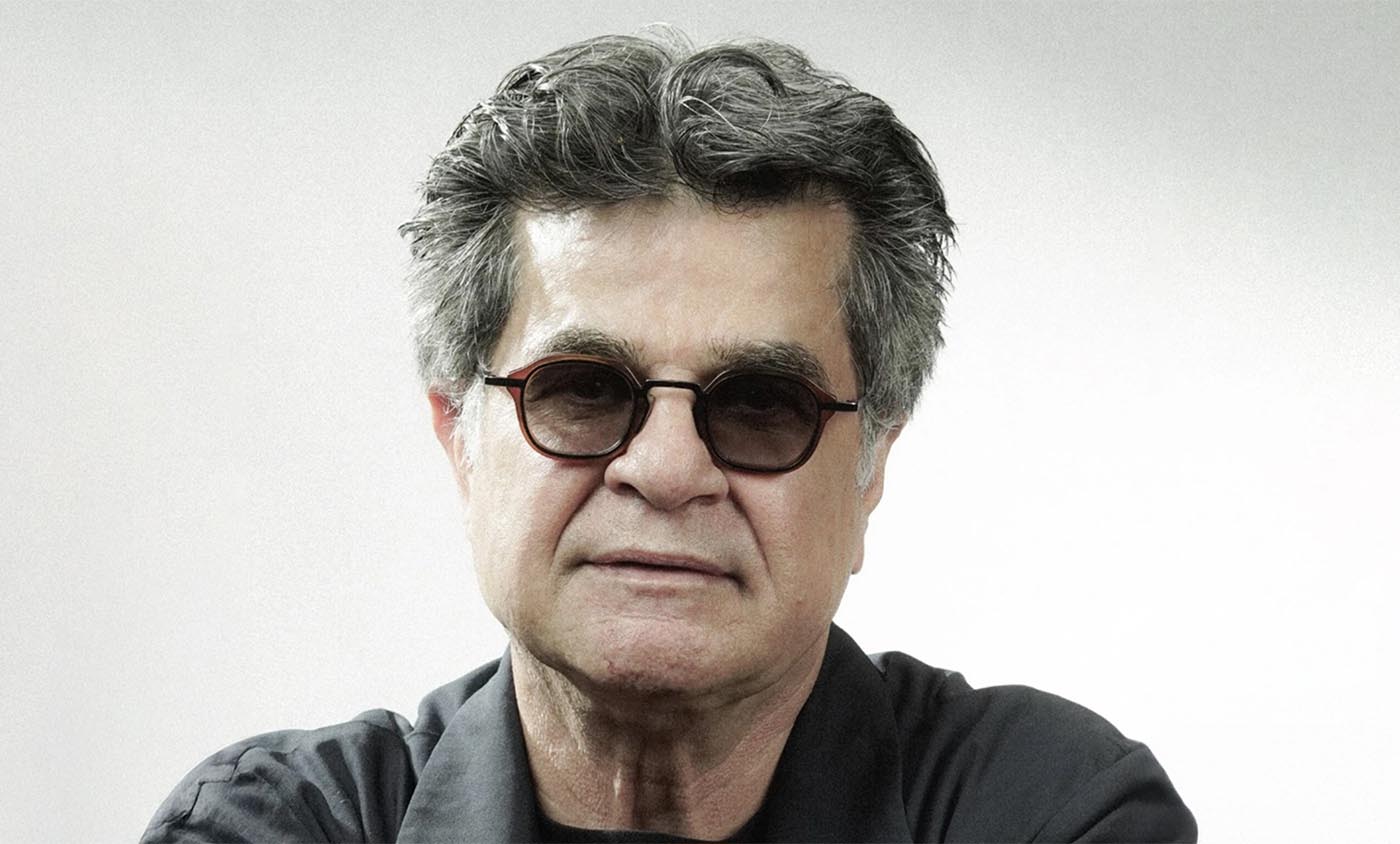

After visa trouble delayed his initially planned visit for It Was Just an Accident’s premiere at the New York Film Festival, I was able to catch up with Panahi at Neon’s Manhattan offices the following week. Our conversation covered what the word “accident” means to him, how he leveraged sound design in the film, and why he seeks to discuss rather than depict violence.

When I hear the word “accident,” I think of an individual mistake or a cosmic misfortune. What does “accident” mean to you or within the Persian language?

In the context of this film, it’s what the parents explain to the kid: It’s an incident that foresees or prevents a bigger incident. In religious belief, certain things happen with the intention of preventing bigger incidents. This is even spoken in the film by the mother, who says that this happened in order to prevent certain problems. But the problems did happen.

Given what a prominent role sound design plays in the final scene, how do you approach heightening this sense in It Was Just an Accident?

This script was altogether based on sound, and it was the kind of sound that we planted at the beginning of the film. We planted its seeds, and in the end, we got the fruit. But this was still one of those films that I wasn’t very clear about the ending. But, at some point, I became certain. I knew that scene had to happen, and that it had to end with that sound. I had shot scenes in which [Vahid] was saying dialogue, and I had shot scenes in which he was reacting with his body. But I took everything out, and I thought any dialogue I put there was redundant. It’s stating the obvious. There are certain things that you design from the beginning and stay true to. Then, there are other things that, for the sake of the film, you have to let go of.

Other than this, there were many other instances in which sound was our main factor. For instance, where they were shooting for the wedding, around that garden, I knew that I had to play a lot with sound [in a] busy [way]. I had to bring out the sounds of crows, because crows in Persian symbolize spying and taking the news. When we were shooting, there were no crows in the image, but we added the sound of crows in special effects. There are certain ideas that you may not have thought about before in advance, but the location gives you the idea. Or, where they are shooting again, you see chandeliers, and their sounds had to come and go to fill the gap of music. The jingling of the chandeliers itself became music.

How did you decide to begin the film the way that you do, following Eghbal in a way that shows both the highs and the lows of his humanity? For a moment, you’re maybe even letting us believe that he’s the protagonist of the film.

You see [him like that] at the end of the film because [he’s absent] in the beginning and throughout. At the end of the film, he needs a bigger share of the image because other characters had taken away his share before. They kept talking about the person who was not seen. He was kept inside the box. Now, he had to be seen, and the rest had to be around him as periphery.

Setting films inside vehicles has become a practical way of filmmaking for you because it’s so much easier to do clandestinely. But even before your imprisonment and censorship, your films often featured long sequences in cars, taxis, or buses. Is this just a way for you to present a cross-section of experiences and people in Iran, or is there more to these settings?

It’s only in two of my films, Taxi and this film! [laughs] But in films that are made clandestinely, there’s a security reason, especially when you work in the city. And especially in Taxi, the point was to hide the camera so no one could see it. But here, the van played a dual function. One, it was because of the content of the plot. It had to be hiding the corpse, and it had to drag people inside it. But it also had a security function, and that was for us to keep taking our equipment around—and especially to hide the camera so we wouldn’t be seen from outside.

I was struck by Shiva’s line when she hesitates to join Vahid in interrogating Eghbal: “I am only just now resuming a normal life.” I think it could just as easily have been said by someone in your position after being imprisoned. What gives you the strength to face these forces rather than forget them?

Just the fact that I love my work. I want to make films, and nothing can stop me. And I just sense that I don’t know anything else other than what I’m doing, so I put all my effort into finding a solution to make my films.

Your presence on screen in the films that you made during the ban says a lot. Was there anything that you took away from the experiences making them that informed the making of this film?

Yes, for instance, Mohammad Rasoulof and I wanted to make a film together [about former president of Iran Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s disputed 2009 re-election]. Because we didn’t have any experience [making films in secret], we sat at home in my place, and they raided the home. So with the next five films, I just kept gaining experience that helped me make this film, and [those films] helped me observe security measures.

With one notable exception in It Was Just an Accident, you depict violence obliquely, such as from a distant camera angle or hidden in shadows. Is there an overarching philosophy to how you depict acts of human cruelty?

I’m not really trying to depict violence, but I’m trying to talk about it. I allow the audience to depict it for themselves, to imagine it based on the definition that exists of violence. If this were a mainstream film, you would definitely see flashbacks and scenes of violence. What you refer to as how to depict [violence], it’s by not showing it that we try to get the audience involved. Every person has their own definition of violence, and when they make the images based on that definition in their mind, then the violence becomes stronger. Like [with] novels and stories, when you read them, and then you see a film about them, you don’t tend to like the film as much. You like what you read. Why? Because we each have made our own images, and no one knows how to make the image for us the same way that we do it for ourselves. If I were to just show very bloody images of the characters beating each other up, it wouldn’t have the same effect that comes out of their talking about it and letting the audience imagine it.

Sound was the one thing in prison that you could count on without your sight, and the ending introduces the idea that even that sense might not be trustworthy. Was your experience that, rather than heightening it, sound just became more suspect?

When they interrogate you, and someone is behind you, your eyes are closed. You’re in front of the wall. All you have is your sense of hearing, [so] you make images based on what you hear. You start imagining how old he is, what he looks like, but you’re constantly in doubt. Nothing can create doubt as well as sound. Even at the end of the film, we show that there’s a white car that comes into the frame. But when you hear the sound, you’re still in doubt. “Was this really the person who came back, or was this something in my mind?” I’d say, yes, [that I’m] in agreement with what you said—[that] you can create a lot of doubt with sound.

Thirty years ago, you recounted a story about a woman who told you after seeing The White Balloon, “I want to believe Iran is this, that the cinema of Iran is this. I want to keep all these memories in my mind.” Obviously, this film has a very different tenor, but if someone came up to you and said that about It Was Just an Accident, would that be correct? Is this, too, Iran in its own way?

Seeing this film, I hope for people to say that the closed system, a dictatorship, will bring these issues with it. The girl in The White Balloon has grown up and, in my films, has become an adult. She’s not just thinking about her own country. She’s thinking about the entire world and believes that these incidents don’t happen anywhere else. Even if the kid sees signs in places that are not believable for those things to happen.

Translation assistance by Sheida Dayani

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.