Author Linda Rosenkrantz first found success in 1968 with her “nonfiction fiction” novel Talk, which she derived from recorded conversations of herself and two friends in Long Island. Rosenkrantz returned to tape as a medium in 1974 for another project in which she asked her artist friends, such as Chuck Close and Peter Hujar, to recount their day prior. The transcript of the latter interviewee’s experience would later be published as the book Peter Hujar’s Day, which fell into the hands of filmmaker Ira Sachs and inspired his latest film.

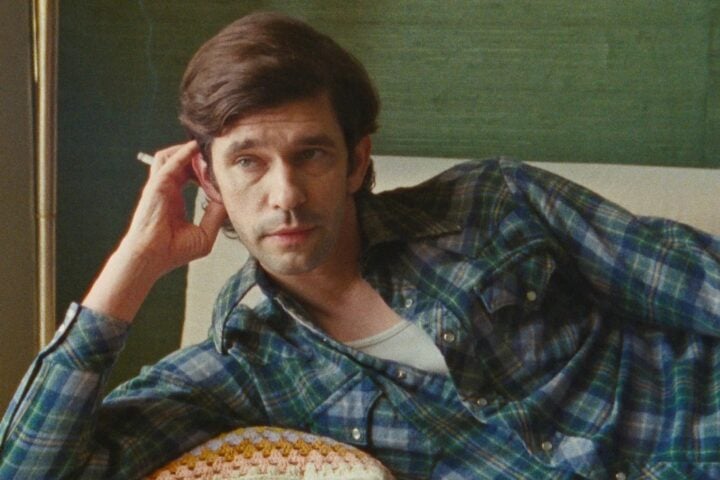

Sachs’s slender yet sophisticated feature adaptation of Peter Hujar’s Day undeniably belongs to its subject and the actor embodying him, Ben Whishaw. But the film amounts to more than just a monologue of Hujar running through various encounters with his contemporaries, like Allen Ginsberg and Susan Sontag, and gradually opening up to making small concessions of vulnerability. Peter Hujar’s Day is a film about the attention and affection paid by those willing to provide the space for an artist to reveal his process—and himself.

Rosenkrantz, in reality as well as through Rebecca Hall’s on-screen portrayal of her, and Sachs each help burnish the legacy of a pioneering queer photographer, who never saw the recognition he deserved in a life that was cut tragically short due to AIDS, by locating the vast beauty within the banality of his everyday life. Sachs’s film resembles the very type of plainspoken but psychologically penetrating portraiture Hujar himself might produce.

I spoke with Sachs and Rosenkrantz just before the theatrical release of Peter Hujar’s Day. Our lively conversation covered how to listen to a subject, what attracts them to the everyday lives of artists, and whether Hujar would enjoy the spotlight the film shines on him.

Linda, what do you remember about this day? How does this representation interact with your memory?

Linda Rosenkrantz: I just have a very general memory of it. I don’t remember specifics of it, [as] it was a long time ago. But the film very much captures the relationship between me and Peter.

I watched the film a second time and was really able to focus not only on form over content, but also on how Linda plays into the conversation on screen. How were you each calibrating how present to make this interlocutor in Peter Hujar’s Day, both in terms of interjecting in actuality or when to cut to Rebecca Hall in the film?

LR: Rebecca did a magnificent job of capturing how I would have responded to Peter.

Ira Sachs: Rebecca serves in the film as an actor, a performer, but in a unique way, she’s also a writer of the film. As an actress, she’s someone who creates text and subtext in silence. She’s incredibly focused and has this concentration which serves, to me, as a form of language. One of the things she understood, maybe more than even Linda or I did, is how much this was a love story about a romantic friendship between two very different people who somehow found each other. Rebecca tells the story of love, and ultimately, she tells one of loss as well.

It’s my understanding that both the book and the film feature some different pieces of the transcript of the conversation. What were each of your considerations in what bits of the conversation would stay in or be left out?

LR: In the book, it was pretty much verbatim. I don’t think there was anything left out.

IS: [interjecting in singsong voice] That’s not true, Linda! Everything is editing. I think in publishing the book, Jordan and Francis, the two publishers, in working with Linda, did make some cuts, which weren’t profound. They just existed. I went back to the original transcript and found two or three things that weren’t included, including the conversation about Bette Davis and John Crawford, which occurs late in the film, [and thought] about which one Linda would want to see, or perhaps [which one she wouldn’t] want to see. I saved that one more essential, almost ephemeral, moment from the dustbin of history, which I feel good about.

That being said, the film is also an edited version. Ultimately, if things didn’t work cinematically, we took it out. So neither is complete, but in neither was a word added. That’s what I would say. There’s no language that we added to the film. We just took out a few things, and there were two things that I didn’t add that weren’t in the transcript that will go unnamed because I felt that they were just a hair impolite, and I wanted to protect both Peter and Linda.

LR: [laughing] You’ll have to tell me privately!

IS: I will! I was talking to someone who was feeling bad for Ed Baynard, whom Peter talks about. But then we decided that, in a way, what he says about Ed Baynard is because he actually loves Baynard. He’s close enough to him to diss him. I like how comfortable Peter is dissing the people he’s close with. I find it comfortingly familiar. The thing that sticks out for me most as the film lives on and I see it over time—and the thing that I, as an audience member, care the most about and get the most from—is how vulnerable Peter is as an artist and someone who’s trying to create things in this text. I feel that is the rarity of the film, which is the window into someone we think of as a master. But even our masters have fear.

When I interviewed Ben Whishaw about Passages, he told me that Ira always wants to focus on “the everydayness of things, how people actually behave in everyday life.” That sounds a lot like Linda’s original aim in having these conversations with artists. What’s at the root of that interest?

LR: Well, my work in general, I’ve done a lot of work with tape recording. That’s all about recording the everyday. I wrote a novel called Talk, which was three people talking about their everyday lives. So, for me, it’s very much a part of what I’m interested in.

IS: Marshall, I never made the connection between Linda and me around that, but I think it’s very accurate and astute. I like that. I think probably that’s very viscerally why I was attracted to this material. It gave me the thing that I’m always looking for, which isn’t the everyday, it’s the authentic. It’s the intimate that comes within the everyday. But it isn’t only because of that. It just feels like we’re so connected to these people, to this time, to this relationship, and to this day that Peter lived because of the details of his narration. I have to say, his narration seems ordinary, but it’s actually very extraordinary once you get to know it better. This isn’t what most of us could do. In his language, he’s actually a great writer.

When talking about telling the story of things that happen in our lives, Charlie Kaufman noted that we add perspective with distance, and that an incident begins to resemble “reconstruction with meaning.” How do you each conceive of the nature of stories and what it means to tell them?

IS: There’s an artist named Max Schumann, who ran Printed Matter [a non-profit bookstore and arts organization in New York City] for years and years and was part of a collective of artists that was known as Cheap Art, that came out of the Bread & Puppet theater in Vermont. Max painted this series of little paintings on cardboard, and they just say, “Tell your story, tell your story.” I’ve always kept that on my wall because I feel like, in a way, he’s validating this obvious concept that our stories are meaningful. But, also, he’s giving us permission to do that. The permission to think that our local story, our New York story, our story of one block or one relationship or one day is significant is a radical thought. The world tells you you’re insignificant. The world tells you specifically, if you’re a broke, gay artist living on 12th Street and Second Avenue, where you’re just trying to make ends meet, you don’t have value. This film gives value to that life in a way that sometimes I need as an artist, and I think other people need as well.

LR: I keep thinking how Peter would have responded to all this attention and praise. It would have made him so happy.

IS: I don’t know, Peter seems like he would have been grumpy about something!

LR: I reject that.

IS: You know Peter better than I do!

LR: I hate all this focus on his grumpiness, his difficulty, and his temper tantrums. That was the smallest part of him.

IS: I’m not talking about that part. I’m really saying that he was able to look at everything in its opposite. That’s what I sense in his work, and I sense it in this story as well. He wasn’t a simple reader, and there was always a flipside to something which was, for him, not just negative. It was the opposite. It was actually just more interesting. Would you agree with that?

LR: I would agree with that.

Ira has described the film as working in “portraiture,” which is, of course, Peter Hujar’s medium. For either of you all as a director or an interviewer, is part of the task of your artistry to be a mirror of your subject?

IS: To some extent, I’m creating a representation of a character. But, with an actor, I’m reflecting what they’re giving me. My role as a director is much more like what you’re describing than as a filmmaker, because I try not to impose. In that way, very similarly to Linda and also a therapist, I try to create space where the actor can reveal things that I can’t imagine while simultaneously feeling observed, cared for, and loved. I think that’s what Linda is really doing in the story, particularly through Rebecca’s portrait of her.

LR: I very much let people reveal themselves in the recordings I’ve done that way.

IS: You’re a great listener. What elements of listening are most important for you? I’m curious.

As am I!

LR: What’s important about listening?

IS: What do you think are the qualities of listening that give people the trust to tell you so much?

LR: Well, giving them my full, sympathetic attention.

IS: I think it’s also a kind of curiosity. The curiosity, at least as I understand it in this text, is pretty endless. It doesn’t have boundaries. You don’t lose interest.

LR: No, I don’t, that’s true. Yeah, it’s without boundaries. It’s interesting, people make so much about this particular day being so filled with people who were or became celebrities, but I think it was a typical day for him. If he had picked another day, it would have been very similar to the phone call to Susan Sontag and things like that.

IS: I imagine the same. I think it was a very full world that he was a part of that played out, in a way, much more regularly than perhaps for us today. Meaning, the cycle of seeing friends was on a weekly basis, not on a monthly or yearly basis, which I think is more common in 2025.

LR: We spent so much time on the phone. I was on the phone from the minute I got home from work, talking to friends, sometimes for hours. It’s very different from emailing and texting.

Do you think that itch is being scratched through texting and social media? Or do you see it as two entirely different things because the nature in which we communicate with our circle has changed that much because of the technology?

LR: I think it’s quite different. I don’t think that itch is being scratched, really. I think it was very different. Hearing voices on the old landline phones was very different. Just hearing a phone ring, your senses would respond, and you would settle down for a long time.

IS: Answering machines, those records of the people in your life [came] into your space in a very actual way. The challenge for me is to be non-nostalgic, to try to figure out how to describe the past and with perhaps some longing, but not with rejection of the present. Then you just feel old.

How has each of your artistic works affected the way that you think about time? Peter Hujar’s Day makes us feel like we’re a part of these very intimate conversations and recreations that are so in the moment, but the second that you record anything, it’s the past.

LR: For me, I very much live in the past. These days, I’m working on another book with transcripts from the early ’70s, so it brings me right back to that period of my life. Perhaps I spend too much time in the past, but it’s fun.

IS: I think that I get strength from the past because I need to see people who were working against the norm in what appears to be a fearless way, even though, as Peter reveals, it wasn’t. [I need to see people] who want success but find it in ways that are more intimate and communal than global or economic. Specifically, as a queer person and artist, I love the fact that there have been artists like Peter who value the world that we live in and the world of us, as opposed to the dominant culture. To make space for the marginal is still a challenge, so Peter inspires me.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.