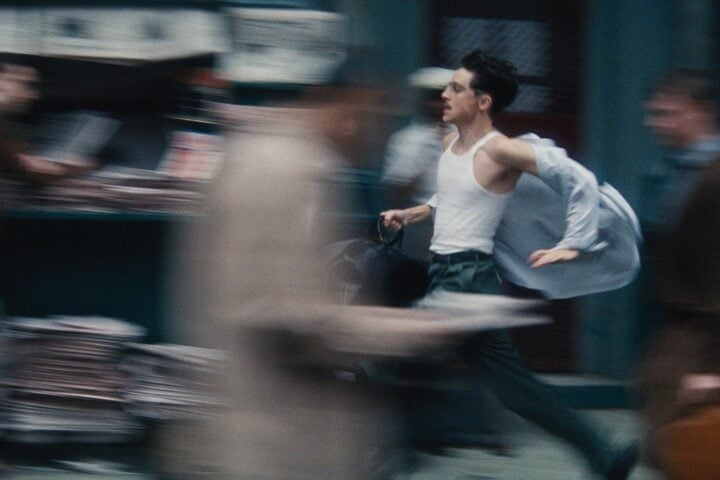

Adapted from Jordan Harper’s 2017 novel of the same name, She Rides Shotgun starts out promisingly, with Nate McClusky (Taron Egerton) picking up his daughter, Polly (Ana Sophia Heger), from school. With his lithe, tattoo-covered body, the scowling skinhead makes for an imposing figure, and Polly doesn’t seem thrilled about being in his presence. It doesn’t help that the car he’s driving is obviously stolen, and she clearly doesn’t believe him when he tells her that her mother is just fine. We’re not sure that we should believe him either.

This opening stretch captures the characters of the book as well as the character of its setting. The Californian desert is shot to highlight the burn of its sun and the brutal beauty of its landscapes. It instantly feels like the place that would produce a man like Nate, who Egerton plays with a mixture of eerie calm and coiled fury. And it immediately feels like a place where a tiny, gentle-eyed creature like Polly couldn’t possibly survive.

The problem is that Nick Rowland’s film doesn’t seem to have faith in the story the novel tells from this point on, which is odd given that Harper himself is one of the screenwriters. The core of the narrative is a Lone Wolf and Cub-style tale as Nate and Polly go on the run together while being hunted by a neo-Nazi gang called Aryan Steel. He teaches her to fight and toughens her up while she brings out his humanity, and their relationship steadily thaws. But the film rockets through this evolution so quickly that it all feels unearned; barely 10 minutes of screentime pass before the two of them are cheerfully eating chips together in a motel room.

Having rushed through the thorny father-daughter relationship that is the core of the novel, the film is left with the much more straightforward and, frankly, less interesting conflict between them and the bad guys. Nate and Polly hide out for a while and then team up with an honest cop named Detective John Park (Rob Yang) to embark on a fairly ill-thought-out mission to take down Aryan Steel’s leader, Sherif Houser (John Carroll Lynch). Their quest is punctuated by gunfights where characters splash bullets around with no apparent sense of self-preservation, suggesting men engaged in a water pistol fight than a life-or-death duel.

The novel is, like Nate, a lean and muscular, without an inch of fat on it. By contrast, the film pads itself out without ever really cultivating its characters. Park and Houser mainly give the story a white hat and a black hat, respectively, and it’s sad to see an actor with Lynch’s unnerving magnetism blasting away on an assault rifle while yelling about being a god like the bad guy from a straight-to-VOD action flick. Polly, whose time with Nate prompts an unsettling transformation in the book, changes little but her hair color over the course of the film. Even her teddy bear gets a reduced role, nullifying a certain heart-tugging moment near the end.

All of which is a shame because Edgerton and Heger are excellent, and they share a strong chemistry, even if the closeness of their characters strains credibility. Nate has an older, much tougher brother who we never see on screen but whose presence is powerfully felt in Egerton’s performance; for all his menace, Nate wears his tough-guy persona like a hand-me-down that doesn’t quite fit, Edgerton’s eyes often betraying the gentler person his character really is underneath. It’s a highly effective bit of adaptation, the film showing us what it doesn’t have to explicitly tell. Sadly, the rest of the original story’s richness seems to have been left on the page.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.