The ambition of Bi Gan’s work was obvious from the centerpiece long takes in his first two features, Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Clocking in at 41 and 59 minutes, respectively, these bravura unbroken sequences (the latter of which also unfolds in 3D) were clear indicators that the emerging Chinese director could command a camera with the best of them. Now, Bi’s third film, Resurrection, which aims to track nothing less than the entire evolution of cinema, proves that the filmmaker’s ambition remains undiminished.

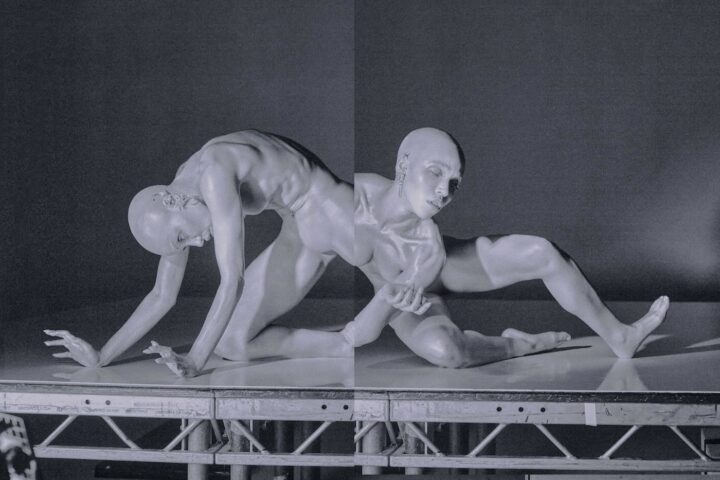

In a dystopian world where humans have traded dreaming for immortality, an android played by Jackson Yee dares to access the subconscious realm by inserting himself into the medium of cinema. “Fantasmers” like him, who disobediently cling to the need for illusions, are targeted by bounty hunters known as “Big Others,” including one played by Shu Qi, who can still discern truth from fantasy. This pursuit plays out thrillingly across five chapters that span the development of the art form within the 20th century.

Not content to merely span from silent filmmaking to the Y2K-era Asian new waves, Bi also maps each section to one of the five human senses. Resurrection ultimately ends with a coda that exists apart from time entirely, as it explores the mind. The filmmaker asks nothing short of surrender from his audience. Those willing to offer themselves up for immersion will find Bi operating on a level of technique and world-building that few others would dare to attempt.

I recently spoke with Bi about Resurrection. Our conversation covered how he translated his narrative ideas into a sensory dimension, what he makes of the connection between dreams and cinema, and why he worries for the future of storytelling.

How do you see the relationship between film and dreams?

I truly believe they’re of one thing. The reason for this is that people tend to think of dreams as something without logic. To me, that’s not the case. I do think that there’s some inherent logic to dreams rooted in our subconsciousness. Usually, these subconscious feelings tend to be very hidden and not as “linear” or orderly as other rational logics, as we define them in a real-life awakened state. There are different ways to tell a story in film, very much like different dreams we might have. You might have films with a very clear, simple storytelling mechanism and narrative arc to express what the creator wants to express. But films can have a hidden, not-so-explicit logic. They might seem a little bit chaotic, but still, there’s a certain logic to it. Not in a conventional sense, but in that dream-like subconscious sense. That’s the kind of film I make.

Do you engage with the science of how dreams or memory work, or are you treating them in an entirely poetic or phenomenological realm?

I’m not a scientist. How I’m going to tell my story artistically is my perspective. Kaili Blues is about time. In one particular scene, you will see how the boundary between the past and the future has been somehow transcended and blurred, and that’s by design. That’s my artistic expression. I want people to feel that type of time that I have created artistically in my film.

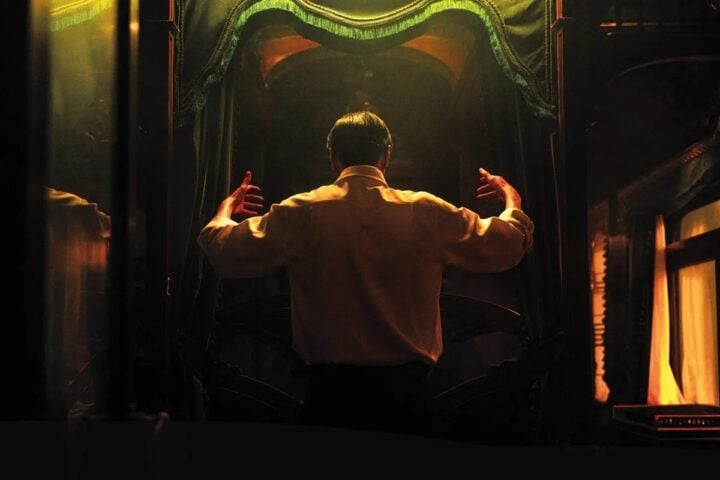

Whereas for Long Day’s Journey into Night, it’s very much about memories. The way I use Huang Jue to play the character in the theater, putting on 3D glasses and then transforming into the long take, is to bring out the textures of the memories through that particular artistic device. It’s also for the audience to experience what I want them to experience.

Similarly, for Resurrection, there would be a different way to deal with dreams scientifically. But for me, it’s about artistic expressions of how I can create this particular dreamscape using the filmic language within that particular century in different styles, forms, and genres.

Invoking sight, sound, and touch are fairly common in cinema, but how did you conceive of a style that would conjure smell and taste?

When we have this particular device to traverse the 100 years that I want to cover, we created this movie monster. Then, the next task for us was to deconstruct this particular character. Not to physically dismember this particular movie monster, but for me, it’s about how we’re going to deconstruct the way this big theater monster perceived the world. For this film, it’s through those five sensory channels that we have to somehow make sense of the world we live in.

Indeed, it’s really hard to somehow present the sense of smell and taste through film, because, for the most part, watching films is very much a two-sensory channel task of audio and visual. For us, we’re using the device of the snow and the white backgrounds to represent in the story the guilt and the punishment that the character experiences. We tease out the taste of bitterness. For me, that’s what bitterness tastes like. Moving on to the sense of smell, I do think that this is also a big challenge. But because the story itself is very much based in this important device of smelling something, it’s almost like an ESP of this particular character. I want to somehow use narrative as a vehicle to carry the sense and bring it forward.

I haven’t seen much discussion about the humor in the film, especially in the fourth section with the magicians. What’s your approach to bringing some levity into such a cerebral work as Resurrection?

I think I’ve been quite humorous throughout all the films I’ve made thus far, including Kaili Blues. There’s this one scene of someone weighing the fish, and instead, the person is actually standing on the scale himself. For me, that was so funny, but some of my crew members didn’t get it. Something that I’m trying to achieve is to make those humorous, light-hearted moments not out of place in the narrative that I have for that particular segment, vignette, or chapter. It’s very much like what I have seen from David Lynch. This might be a scary, strong scene, but at the same time, there’s also an element of humor and levity. It’s just so seamlessly integrated into that particular narrative, so that’s what I’m trying to accomplish with my films as well.

There’s a running motif of a candle throughout the film, and its burning out is correlated with cinema itself. Is this indicative of your feelings about the medium?

The viewer might have different interpretations, and I think they will be just as valid. For me personally, I really want to use the motif of candles, especially the cinema at the end, to really reflect on what I feel about what’s already going on right now. In the past few years, the spiritual homes that we used to have—in this case, a theater—have slowly been torn down, taken away, or somehow demolished. It was once concrete, and it’s no longer there. We won’t be able to get it back, ever. That’s what I’m trying to accomplish with that last device.

I know the title in English is different than the title in Chinese, but is cinema in the process of resurrection…or in need of it?

I do think that film as a medium will always be there. I’m not trying to say that somehow this particular art form, or cinema itself, has either disappeared, will die, or has died already. What I’m trying to express is the stories that we are telling now and the ways we think about art are very, very different. I’m worried. I’m very concerned about the future of storytelling, about how we envision the nature of art, especially with technology going forward. My concerns aren’t so much in terms of film as an art form. I think it’s always going to be there because, as human beings, we tell stories. That’s in our blood, and that’s what we need as a species. Film is a byproduct of that. The subject of storytelling, and what kinds of stories we tell, are my concerns. Not so much in terms of film as an art form, or cinema as a physical structure, or as a concept.

Translation by Vincent Cheng

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.