One question is given special precedence throughout writer-director Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia: “Who owns our days?” Toni Servillo’s Mariano De Santis, a fictional Italian president, gradually evolves to arrive at his own answer. “They are ours,” he wistfully imparts to a journalist, “but paradoxically, a lifetime is not enough to understand it.”

The film serves the same purpose for us as it does for its protagonist: illuminating what gives value to existence. La Grazia translates into English as Grace, though the term has a second and more tangible meaning for President De Santis. It also refers to the pardon power vested in his role, and the end of his term offers an opportunity to exercise it on behalf of two incarcerated men. The circumspect leader considers their pleas for mercy alongside a bill pushed by his daughter and adviser, Dorotea (Anna Ferzetti), that loosens restrictions around euthanasia.

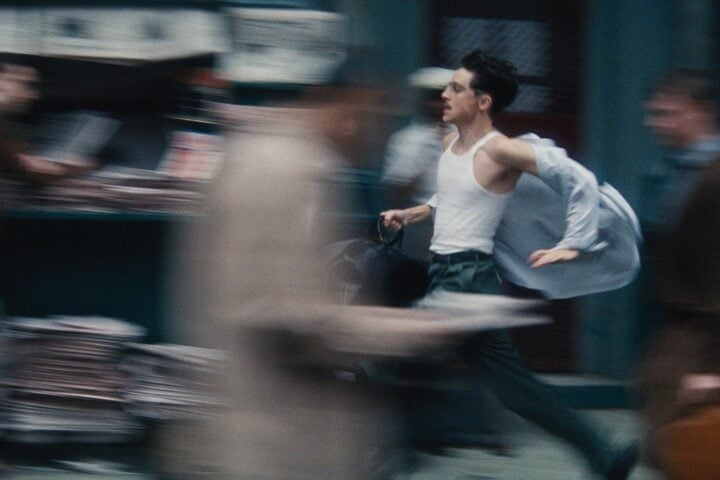

La Grazia finds Sorrentino, regarded by many as his country’s heir to Federico Fellini, working in a more muted fashion as his film dwells in contemplation with the legalistic De Santis. But the Italian director’s trademark vibrancy still manages to peek out in stylized interludes, which tease out the character’s appetite and capacity for change. Sorrentino’s film offers a moving testament to the power of transformation at any stage in one’s life or career.

I spoke with Sorrentino while he was in town to present La Grazia at this year’s New York Film Festival. Our conversation covered what the office of the presidency means to everyday Italians, how he approaches writing characters who are different from himself, and why it was important to reflect an ideal version of politics in his film.

How did you come to open the film with all the text from the Italian constitution about the role of the president?

It’s not always easy to find your way around the powers of a politician like the Italian president, who’s not the prime minister and has a more limited range of powers. Therefore, I thought it was necessary to lay out what a president can and cannot do.

Since the United States doesn’t have a similar ceremonial head, what are the general attitudes toward the president in Italy?

In Italy, the president is sort of the last bastion of democracy. If things turn sour, the president is the last figure of authority that one can turn to. Going beyond those powers, which can be limited, what they do have is a strong power of moral persuasion over the government. And this has traditionally always been quite solid and strong.

You’ve made several films about prime ministers of Italy. Was any of that work helpful in terms of writing this character when thinking about politics and power?

They were useful to the extent that I avoided doing things that I’d already done in those movies. In those movies, I had showcased the show business element of politics. In this movie, there’s none of that. I just decided to focus on the moral dilemma component of politicians.

You’ve said that you’re driven by curiosity about “what happens in the mind of people who are very far from me.” How do you get inside those minds to understand them?

It’s a mysterious process. Other writers, and I’m referring to writers of literature, have said what I’m about to say, and I do agree. They’ve said that when you start writing, it’s as if another self takes over and starts writing instead of you. But, of course, it’s always myself.

What’s the process of taking that and then mapping it onto Toni Servillo?

When I write my script, I often don’t even tell Toni that I’m writing with him in mind. Then, when I’m done, I have him read the script, and we start talking about it. There’s a first stage where the actor, and in this particular case, Toni Servillo, has grasped some but not all aspects. But maybe they’ve also grasped some components that I wasn’t aware of, so we start this exchange process in which we discuss the character. This process continues over time, takes shape, and becomes much more real when you get to the stage of trying on costumes, makeup, and hair. You start that transformation process where the character takes shape.

This film feels less cynical about politics than your prior work. Is that rooted in a desire to create the grace on screen that might be missing in reality?

Yes, it’s exactly that. I wanted to tell the tale of a politician who’s exactly the way I would like to see a politician to be.

Do you, like De Santis, wrestle with the nature of your job? Not to suggest that you’re “reinforced concrete,” De Santis’s nickname, but is there a tension between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law in filmmaking?

In minimal part, yes. Of course, my dilemmas as a screenwriter are nothing compared to the massive dilemmas that a president can have. But having said that, yes, the script is sort of like a prison cell, and it can be hard to find an evasion route out of that cell.

You’ve noted that De Santis’s relationship with his daughter pulls from some of your own experience. Is opening up your own life more to the films something that stems from making an autobiographical film like The Hand of God?

I’ve always had that approach, ever since my very first movie. This was a strange mix of some autobiographical elements combined with things that I invent and things that I like.

The film has many moments of big aesthetic expression, such as the slow-motion sequence of the Portuguese president tripping in the rain or those rap beats De Santis hears. Are those coming to you as part of the original conception of the scene, or do the visualizations come to you later?

I have them in the script already. I visualize them before I ever shoot.

I saw the film in Venice, and I could tell local audiences were reacting very enthusiastically to the cameo from the rapper Guè. For those less familiar with this figure, what should audiences know about the significance of his inclusion?

I wasn’t familiar with his work either. He’s a rapper whose song “Le Bimbe Piangono” I like. And the reason I like it is that I perceive that [beneath his] rapper [façade], he’s hiding a very deep, delicate part [of himself that] shows that he’s a man who’s gone through a lot of pain and suffering. This pops up in his lyrics here and there, and I like that. But I don’t know him, and it’s not the kind of music that I listen to on a regular basis. I have the same approach toward him that the president in the movie does.

Did Guè’s line about how “Sorrentino couldn’t have done a better take” in the song come about before or after your collaboration?

That’s an old song, so it’s before!

Translation assistance by Lilia Pino Blouin

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.