Writer-director Carmen Emmi’s Plainclothes is striking for how timely its story of a closeted undercover police officer feels despite having its eye trained on what we’d like to consider a less enlightened time than our current one. Set in the late ’90s, Lucas (Tom Blyth) is tasked with ensnaring gay men at a mall cruising spot, but after he falls for one of his targets—the older, also closeted, but world-wise Andrew (Russell Tovey)—the film becomes a potent examination of social shame and the tragedy of compromise.

Though some might say that stories centering the gay traumas of yesterday are outmoded and have little left to tell us about where we are now, Plainclothes makes the recent past achingly present. Told in a hauntingly humane and richly fragmentary style, the film draws from a history of police operations targeting gay individuals to remind us that everything we think we’ve moved beyond has its echo in what’s happening right in front of us.

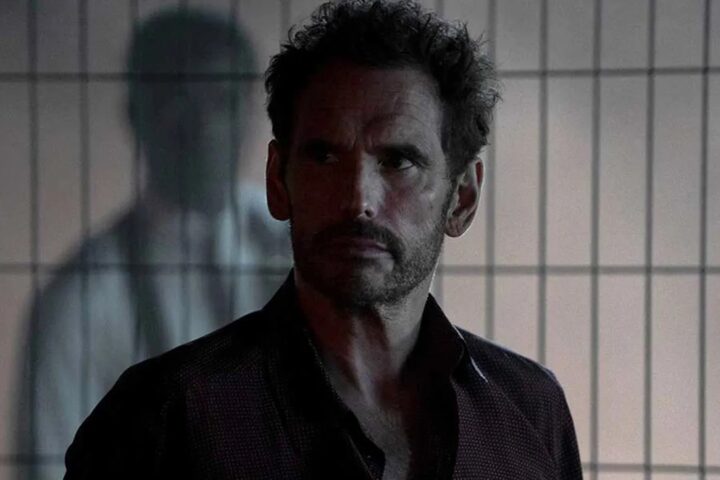

I recently sat down with Blyth and Tovey to discuss the frankness of the film’s sex scenes, how their intergenerational on-screen romance and off-screen partnership enriched the material, and how Emmi’s artistic approach ensured that this was anything but a traditional shoot.

Russ, with credits like Looking and American Horror Story: NYC, you’re sort of old hat at same-sex sex scenes, but, Tom, I think this was a bit of a new experience for you. Can you tell me a bit about what that journey together was like?

Russell: I like being referred to as old hat! [laughs] Yeah, you feel a responsibility for the other actor you’re having simulated sex with because it’s very anxiety-inducing. It’s an odd part of our job that you might not even know someone, and then, day one, you’re there pretending to bum them, and that can be daunting. But what Tom and I had is that we both believed in this film so much, and we believed in the characters and the truth of that [connection]. When they finally have sex, it’s the most beautiful, needed, vital connection that both of them as human beings desire so much and need in that moment. We had an incredible intimacy coordinator named Joey, and it was the clearest choreography for what we were doing. It gave us total freedom, but also our boundaries were safe, and we felt safe with each other. And I think me and Tom just like each other and wanted this to be the best it could be, and that was so important to us.

How did you find the experience, Tom?

Tom: You’re right, I haven’t done a ton of sex scenes before. I’ve been working a fair amount of time, but I haven’t done that much sex. But I’ve done it in real life [laughs]. So, I know what it is!

RT: [laughs] Have you? My God, that’s an exclusive.

TB: As an actor, you’re putting yourself in the shoes of your character and it’s supposed to be an exciting, fun thing when it’s done right. Right? And I think if both actors are like, “Let’s let this be an exciting, fun thing and have fun with it,” and trust each other, it can be an exciting, fun thing on screen. The great thing about this is we’re representing a [character’s first] sexual experience as a good experience. Russell and I talked about that before: how we wanted this to be a good experience for Lucas. So many young people, gay or straight, have really bad first experiences, and, I think, especially in the gay community, there’s a lot of anxiety involved. We both felt like it was an honor to be able to represent a good experience for [this character] as his first time. The character of Andrew is a mentor to Lucas and Russell’s one of my heroes, so I wouldn’t call him a mentor because I wouldn’t put you in that position, Russell, but…

RT: Just old hat.

TB: Yeah, that’s right! [laughs]

TB: And there’s that beautiful mirror to real life. So, long story short, we just trusted each other and wanted to honor the characters.

RT: What was also important to us is that the sex was safe because of the time. Andrew wants Lucas to be safe, and he wants him to have a great time, but he also wants to educate him. Because it’s 1996, ’97 where it’s set, and it’s a terrifying time still. I think that’s why we see the condoms appear so clearly, because it’s telling us where both of the characters’ heads are at.

This is all very refreshing because we’re in a very sex-negative time, especially in cinema, but it seems like queer directors like Carmen Emmi, Andrew Haigh, and others are still keeping the torch lit and pushing those envelopes. What do you think the value is in showing sex on screen in a film like this?

RT: I think it’s the human condition. I think you have to prove the existence of humanity and humans have sex, whoever they are. And the more you prove the realities of people and that they exist, the more we can get over it. I think an authentic sex scene that shows love and connection between two human beings can prove how we’re all similar rather than different.

TB: I think if there’s anything the film shows as well, it’s when you, as a society, repress other people and push their self-expressive acts into the dark, they become more dangerous inherently. And that [repression] is mirrored in how you show it on film. If you can show realistic sex, it takes it out of the dark and says, “This is okay. You don’t have to be shameful.” Taking the shame out of it and making it less taboo is showing it, I think.

RT: I use the word “universal.” If you show us sex between people that want to be having sex with each other, and you make pleasure something that is a human need and want and desire, you’re making something universal. And even though this film is told through these two queer characters’ lenses, it is a universal story about unrequited love, needs, and desires.

Tom, I’m interested in that repression and shame. In the U.S., obviously, we have a rough relationship with policing, especially as it relates to marginalized people. The film reflects that, but I wanted to ask what those conversations were like with Carmen knowing he has law enforcement in his direct family.

TB: Yeah, the reason why the film feels so personal is because Carmen has put a lot of his personal experience in the film. Carmen put a lot of his own kind of coming-out story in there, and his brother is a policeman, so he leaned on that experience. By all accounts, his brother is a very good, very lovely policeman and was very supportive in Carmen’s journey in filmmaking in general. But I did a lot of research on my own into policing, especially undercover policing and the stress that’s involved in that, as well as policing in New York in the ’90s.

We just had another discussion recently, and it occurred to me that when we’re talking about policing, often police look the same. For a long time, police have looked like a certain type of [person], usually men, and if we ever expect these people to uphold the duty of looking after the community, not to punish it, but to look after it, then it needs to look like the community that it’s within. Right? And that means the people involved in the policing conversations should be the community [itself], and I don’t think we’ve reached that yet. And, in fact, right now, unfortunately, we’re backtracking, especially in the U.S on that, and I don’t think that will ever be good. So, I hope that changes, and I hope films like this can help show why it’s necessary.

Russ, you spoke a bit about the scariness of this time. What did it mean to you to inhabit this role and sort of return to this era?

RT: Well, as an “old hat” gay man, I was able to impart my experiences. When I was first thinking about sex, it was very much mixed with death, and I think that’s the same for many queer people. I think it’s an incredible thing that, now, people don’t [have to] consider that, with [HIV] treatment and PREP [having] been revelatory. But I think that [fear] is where Andrew’s at, and I think because Andrew’s a dad, and he’s got a wife, and he’s got this life, and he’s got kids…he’s terrified of it, but he doesn’t show his fear of that time to Lucas. I was completely terrified of it, for sure. Andrew Haigh, he talks about my generation being—I don’t know how old you are, Rocco, you look a bit old hat, but if you’re…

I’m rapidly approaching old hat.

RT: Okay, good [laughs]. We can be old hats together. He described us as the middle generation, which is discovering that they like men at the same time that AIDS is around. So, you aren’t dying from it, but you can still get it, and sex is twinged with that consideration the whole time. Carrying that around was something that I wanted to impart this character with for sure.

Tom, how did you sort of learn about or embrace embodying this era since you probably don’t remember it quite as vividly as Russ?

TB: I don’t worry about playing times that I didn’t live through because I would never do a western or a period piece, and I do a lot of those. Because it’s closer to the time we live in now, and I was a kid in the ’90s, I’m able to remember certain aspects of it, but my experience isn’t the same as Russell’s and never will be. So, in those moments, I just try and listen. Russell is such a supportive partner, creatively, and he’s very generous in talking about his experience. We had a beautiful creative team that was able to bring a lot of their own personal experience to it, and you can lean on your colleagues when you don’t know.

There’s compellingly fractured nature to how this story is told, some very expressionistic flourishes, surreal moments even, and Ethan Palmer utilizes different types of cameras on top of that. So, I’m curious for both of you shooting it, did that fragmented sort of storytelling come through on your side of the camera? Or did it feel like any traditional shoot?

RT: It wasn’t traditional. On the fourth day, they were filming on set and Carmen went, “Come with me.” We went up to this office and he just started filming me with a camcorder, going really close to my face, coming back out. And I was thinking, “What the hell is this? How is this all going to work?” I said, “Is this behind the scenes?” He was like, “No, no. I think this is going to be in the film.” I was like, “What? How’s that all going to come together?” And then, when you watch it, you think, well, that’s why the film is getting the reaction it’s getting, because he’s reinventing storytelling through different lenses in a way that people aren’t. [He’s] being adventurous and experimental, and I’m so inspired by that. But being on set, it was slightly…I couldn’t understand or picture what he was trying to achieve.

TB: I mean, Carmen, he’s a true artist, isn’t he? It wasn’t traditional at all. One day, I had a rental car, and I was like, “I’m going to drive myself to set today.” I like driving. [My character] drives a lot, so I was like, “I want to drive to set in the snow.” Afterwards, we’d had a hard day and Carmen was like, “Can I ride with you?” So, we drove back to the hotel, and we’re kind of talking about the day and how certain things had gone well, certain things were difficult, having a heart to heart. And I’m talking to him, chatting away and trying not to crash the car because it’s icy conditions, and I just see the camera come up. [laughs] Carmen’s filming me as I’m driving and talking. And I was like, “What do you want me to do? Do you want me to be in character?” And he was like, “No, no. Just do it.” I’m like, “But how are you going to use it? I’m not in costume.” He’s like, “No, no. It’s a super close-up.” So, he’s zoomed into my eyes as I’m driving home after a 15-hour shoot, and some of that makes it into the film. He uses stuff like that because he’s never off. Carmen is always on. He just lives and breathes it.

What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

RT: I hope people are going to come away from this film feeling or just thinking about these characters. A lot of people have responded saying that these characters have lived beyond this film for them and they consider them, and they want to know that they’re okay. I guess fundamental now is that safe spaces are being removed for queer people, which pushes us further into the margins, which pushes us further into danger. So, I hope people, again, will find similarities in these characters rather than differences and get some understanding and see their existence and that it’s all okay. And be entertained and discover a new storyteller who’s on the block because I think Carmen is doing amazing things and is incredibly important already and will go on to tell amazing stories. And as a queer voice, we need that more than ever.

TB: All of that. And I suppose I hope people feel seen. I mean, anytime I make a film, I hope people feel they can see themselves in it in some way. But especially a film like this, and especially now. We got a message recently from someone who had seen the film and messaged Carmen and said to all of us, “I’m a Chicago police officer, and this was my life for many, many years. Thank you for representing it. It was honest, and it felt like my experience.” I think there’s a lot to be said about seeing yourself in art, and I think it can literally be like a beacon in the dark sometimes when people are in a dark place.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.