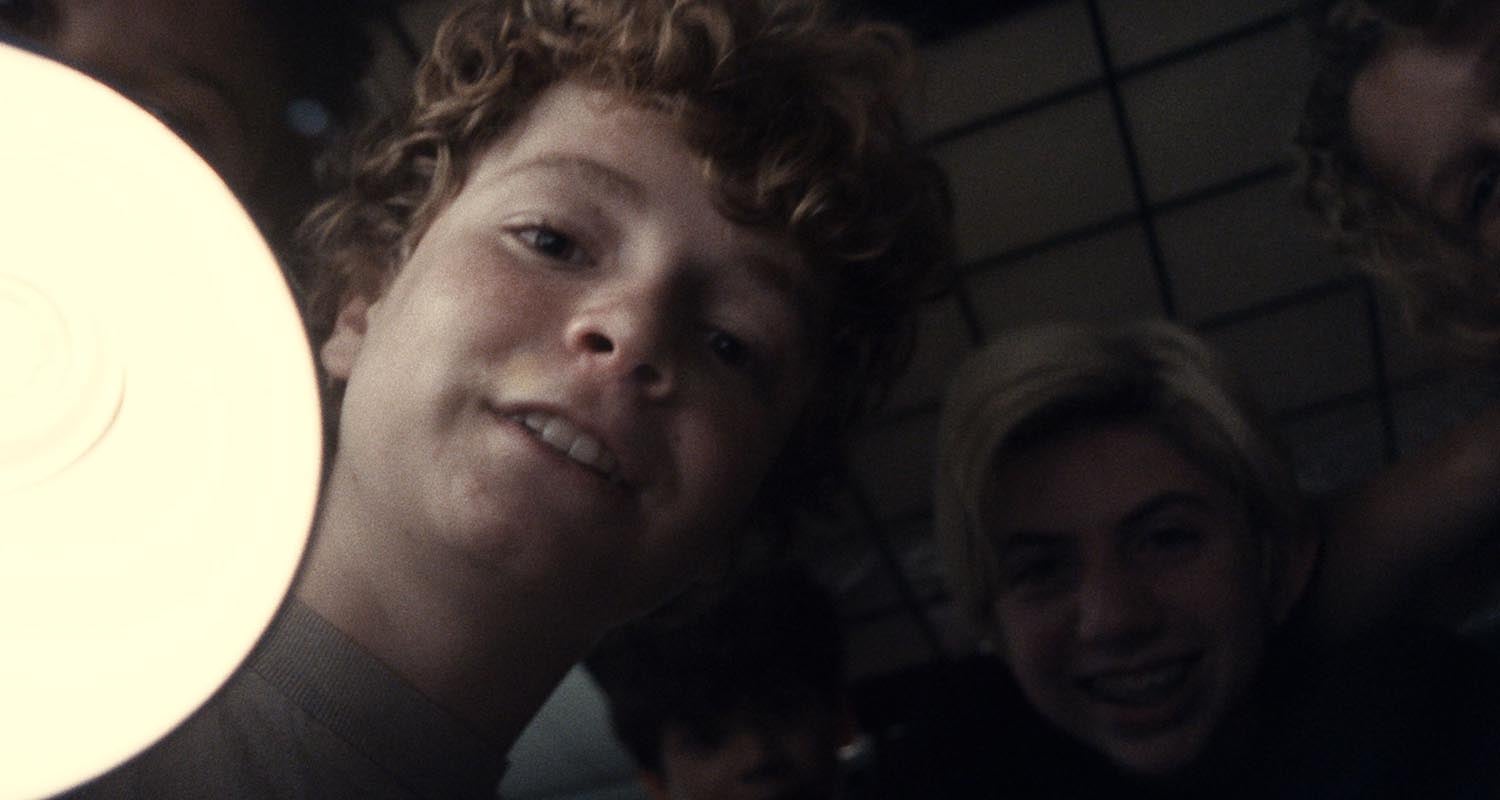

Charlie Polinger’s feature debut, The Plague, expertly captures both the intimate physical mechanics of adolescent bullying and the feelings of dissociation stirred by such psychological terror. Against the backdrop of a water polo summer camp in 2003, Polinger also finds fertile ground to play with horror and psychological thriller conventions.

The film plunges us into the headspace of Everett Blunck’s Ben, a 12-year-old boy just trying to fit in among his peers. The team’s ringleader, Kayo Martin’s Jake, seizes on Ben’s foibles to make clear that his acceptance in the group is conditional. Everyone’s deepest dread is to end up like Kenny Rasmussen’s Eli, the pariah of the group whose skin rash Jake dubs “the plague.”

The playing field in the pool is just one of the many battlefields where Ben feels he must fight to maintain his sense of self and sanity. As Polinger’s masterful orchestration of genre tropes offers a vivid window into the character’s inner turmoil, the filmmaker’s larger statement on the nature of bullying emerges. Anyone can act as both victim and perpetrator in a social structure designed to reward those who can most confidently assert their dominance.

Ahead of The Plague’s theatrical release, I spoke with Polinger, Blunck, and Martin about this uniquely chilling on-screen depiction of childhood bullying. Our conversation covered what was different about bullying two decades ago, how they developed the characters together, and why improvisation was such a powerful tool to unlock the emotion of a scene.

The Plague follows a group of 12-year-old boys. What did it mean to each of you to try to get inside the headspace of that specific age?

Kayo Martin: I was 14 when I played [Jake], but everyone thought I was 10. Playing a 12-year-old, people definitely believed it because, at that point, I still kind of acted like a 12-year-old.

Everett Blunck: I was 14 too, so there wasn’t a really huge difference. With the material of the script, there’s nuance in how kids behave. But bullying is bullying as a teen. For me, it wasn’t really like, “I’m 14 and have to act 12.” It’s like, “How would I act if I were being bullied, or if I was in this situation?” For me, acting younger than myself wasn’t something that I concentrated on. Sometimes, it would be a little more evident, or you’d have to make it a little more obvious that you were a 12-year-old and not like a 14-year-old.

Charlie Polinger: I felt like 12 was a really specific age, and we felt it in the casting process. If someone was even sometimes 10 to 11 or 15 to 16, it would feel really different. There’s a particular age where it doesn’t feel like it’s a little kid, but you’re not quite [a teenager]. Even talking to Kayo and Everett right now, I feel like you guys have matured to a level that wouldn’t make sense for the movie anymore. You just aren’t as vulnerable or young as the dynamics going on here. Even six months after the shoot, I noticed a difference in you guys. I think [that age] is this very particular moment where it’s right on the edge of still being a kid and not anymore.

When trying to recreate the time period in which the film is set, did you find it was more similar or more different from today than anticipated?

CP: I just knew what it was like to be a teenager in the 2000s, and so I wrote from a place of what I knew. I think there are definitely things that feel similar. Obviously, things are really different with social media and phones. But I’m curious if you guys feel like, after watching the movie, it feels really different from your experience today, or not really that different.

KM: I feel like there are a lot of movies that are based around that time for teenagers, so it wasn’t too hard to relate to. But it was definitely a change having to learn the music and not being able to use new slang. All this different stuff came into it, but it was really cool to learn some of the early 2000s stuff and get into Charlie’s shoes.

EB: Now, a lot of [bullying] is more like digital than it is in person. I feel like people have gotten really comfortable bullying behind screens, because it makes it easier. It’s more accessible for people, and you don’t have to show yourself to do it. So that was a big difference because I don’t think bullying is less prevalent now, but it’s definitely taken a different form. So reading the script, acting it out, and seeing it more active and in person than I have seen in real life was interesting. I thought that was cool because, obviously, I wasn’t a teen in the 2000s. There are still a bunch of forms of bullying in person, but I feel like it’s way more direct in the film.

The Hollywood version of this movie would likely simplify the dynamics between Ben and Jake, but they’re more complex than simply victim and bully.

EB: The way Charlie wrote it was really great. You can really see that there’s more nuance to each character. Charlie, the cast, the producers, and the crew were really great in that sense. They polished it in the final cut to see that there are different layers to people. Jake’s a little more insecure, and Ben wants to fit in but also doesn’t want to exclude Eli. That was cool for me to read and see all of the other kids act that out.

KM: That was the thing all along that made it so good. When I was actually first reading it, I was thinking I wanted it to be more straight-on bullying. I would say that to Charlie, but Charlie would be like, “No, it’s better if you just act like you’re getting in his head.” He was swearing to me that it was better, and then I watched it, and it definitely is better like that. Charlie, what were some of the things that we would say on set? You would definitely give me some tips.

CP: It would just be like, “Make him the one who has to be awkward.”

KM: Jake is the most insecure one, but he’s putting on as someone secure in his own way. Ben is trying to be himself and make friends, but Jake is definitely targeting that and fully [bowling him over] with confidence. Every time Ben tries to fit in, Jake has to really pin him and get him.

CP: And you just sit there, look at him, and wait for him to make the next move. That made him lose all the power.

KM: It’s perfectly thought out [by Charlie] how I’m targeting the kids going through adolescence. It’s a water polo camp, so they’re in a pool. Of course, kids are going to get a rash and pimples. Stuff’s going to happen, so I’m targeting the ones that it’s happening to. If I saw some pimples coming on Ben, I’d be like, “Oh, this is the one that I’m going to get, and say he has the plague next.”

CP: We’d do a whole take where it was like a joke, and then we’d do a take where it’s really serious. We’d mix it up, too, and I think that helped create this performance where you’re always on that razor’s edge of [wondering], “Is Jake ever serious?”

KM: Yeah, that’s what makes it really good. As it goes back and forth, people don’t know if it’s a joke or not, like when I’m explaining the plague to him in the beginning. But then, toward the end when the music comes on, I’m really talking about the pimples, and it starts to seem real. I go in and out of it being real and being fake. Which one did you choose more of when you were editing, Charlie? Did you choose the joking or the serious [takes] more?

CP: The really good thing is that by the time I was in the edit, I didn’t even remember which was which. I couldn’t tell myself, so I don’t even know.

Your casting director, Rebecca Dealy, said one of the things that jumped out to her in the script was that it didn’t overly intellectualize the actions of young boys, which is more in line with how 12-year-olds go through life. Did that also apply to production, trying to approach the characters more through instinct and emotion?

CP: I think that the script was always clear on the simple thing that was happening here. Ben doesn’t know the group, and he’s joining the group by trying to sit at the table and just blend in. Jake’s testing him out a little bit. Another thing for Jake was just to always be observing things and be very aware of stuff. He sees this new kid sit down, and you were watching the way he was interacting with the group, paying attention to how he talked, and realized that he can’t pronounce the word “stop.” He latches onto that just to test how he’s gonna deal with giving Ben a little bit of shit. Is he gonna be funny about it? Is he gonna get upset? You’re always testing him. There’d always be a clear “this is what this scene is about,” and then it would just be about leaving room to explore where we took it from there.

KM: A lot of the other bullies, like Matt and Logan, are very outward with their speaking when he comes and sits down. But you can tell that Jake, when Ben’s sitting down, is going to find something to target him with. He waited, waited, and then Ben said, “Sop.”

EB: Charlie had a very clear vision, but he was very open to us trying new things. That’s really important a lot of the time in film because it’s great to have something in front of you [where] you know what to do, what the character’s emotion is, and what the director wants. But to have a relationship with the director and writer that allows you to have more leeway and improvisation was really helpful. He was asking us our opinion on it, and that made it feel more natural for me.

Everett, it’s my understanding that you and Charlie worked together to think about Ben’s emotional state going into a scene, and that would guide the shot choice. How did your collaboration work?

CP: I think we’d try to very simply block the scene without getting too into the performance of it, just to get the shot up. The first time, I’d be like, “Just go for it.” And then, it might be like, “Try letting it find its shape a little bit. Don’t let them see how stressed you are. Try to get this one person to help you out,” with you and Elliott [Heffernan] or something like that. Then, you would lock into the note and try it another way. We would keep finding it. Or, sometimes, I wouldn’t call cut and keep going to see where it took us.

EB: That was the most helpful thing for me. It’s way more natural when you work together and build it organically. Like I said before, it’s great to have something in front of you so you know the basic emotions and basic actions are. But, after that, it’s gotta feel human. If there’s no room for you to do anything different than what it says, or there’s no room for any sort of adjustment, then it’s just going to feel stiff. That helped me get into Ben. Charlie mentioned the scene with me and Elliott, who plays Tic Tac, where we’re eating Cheetos and Doritos sitting against the wall. That was entirely improvised, which I thought was really cool. It was like 20 minutes just talking about whatever, and it felt like a conversation just with him. I thought that was a really cool example of improvisation and what we did going off of each other.

I loved hearing about some of the different rehearsal techniques, like getting acquainted in the various shooting spaces and doing structured improv in character. From each of your perspectives, what was most helpful in terms of building the group dynamics among campers?

KM: Charlie would actually have us doing that a lot in explaining the plague scene. He would film it as we would just walk through the big warehouse that we were shooting in. I can’t remember too many specific exercises. I remember with me and Everett’s acting coach, Jackie, we would do speed read-throughs. She really wanted to make it not about the memory at all, and it wasn’t. Once we got there, since we did it so much, I knew pretty much every part of the script that Jake was in. It was just fully about the acting, and the lines just started flowing out.

EB: We did games. On the set where all the bunks were, we all sat in a circle and played acting games. Just getting to know each other, we had a week of practice in rehearsal for water polo. That was really great to get to know everyone before we started and form relationships with people. When you go in kind of cold turkey without knowing anyone, the dynamic can feel a little off sometimes. It was really great for me to meet everyone, have fun, go to each other’s hotels, and do water polo with everyone before we actually did the filming process.

Having made this film about bullying and social dynamics, does it make you see things differently in your lives outside of the film?

KM: Yeah, I can see it now if some kid is getting messed with on the street psychologically. I can definitely see it so much more. I tell some kids to calm down on some other kids sometimes.

EB: I agree with that. A lot of the time, we see bullying in movies as more physical and direct. It’s not necessarily as psychologically messing with your head. Sometimes, you can’t see when someone’s being bullied. It’s not always going to be very physical or yelling, like giving you a swirly or a wedgie. It’s very real, and I think this film does a really great job of raising awareness that it’s a very real thing that’s going on right now.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.