“We have a lot of people in this movie who don’t act,” erstwhile businessman and TV personality Kevin O’Leary recalls remarking on the set of Marty Supreme. This observation prompted director Josh Safdie to respond, “Who said they don’t act?” O’Leary explained, “Well, they’re not actors.” The filmmaker then retorted, “What’s an actor?”

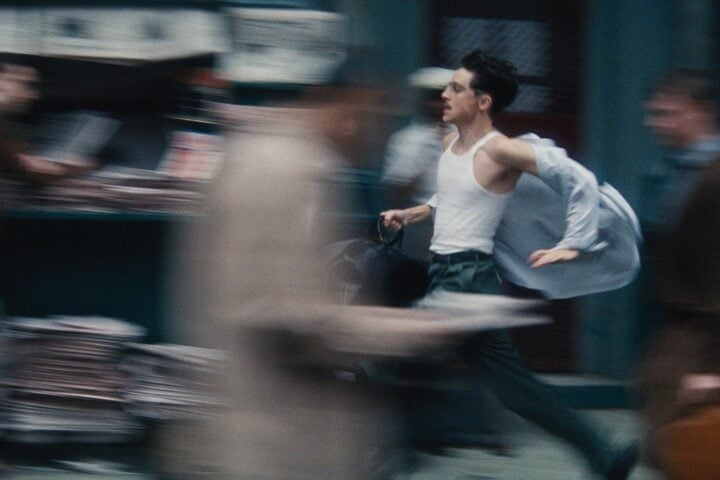

Safdie’s body of work has long made space for non-professional actors, who amplify the realism of the stories he tells. Indeed, the authentic local color and personality that’s conveyed by Marty Supreme’s vision of New York City in the early 1950s would be impossible without the presence of such figures as NBA legend Tracy McGrady, online sports personality Luke Manley, filmmaker Abel Ferrara, and even grocery store owner John Catsimatidis.

But Safdie’s ultimate casting coup in Marty Supreme is Kevin O’Leary in a major supporting role as Milton Rockwell, the wealthy CEO of a pen company. Despite appearing for many years on the reality competition show Shark Tank, the film marked O’Leary’s first scripted role. He leverages this background masterfully as the embodiment of an old-money establishment ethos. This makes him quite a potent capitalist foil to Timothée Chalamet’s Marty Mouser, who brings an upstart entrepreneurial energy to his quest for greatness.

I spoke with O’Leary ahead of Marty Supreme’s Los Angeles premiere, as he was still digesting seeing the finished film for the first time. Our conversation covered how his improbable casting came to be, what he learned from working alongside Safdie and Chalamet, and where he sees some of himself in Marty’s striving for success.

You’ve said that Josh Safdie and Ronald Bronstein’s pitch to you was that they needed a “real A-hole” to play Milton Rockwell. Do you take it as a compliment?

I heard it before, 20 years ago, from Mark Burnett when he was casting for Shark Tank. He said exactly the same thing. We were just having a random conversation. It was supposed to be breakfast, but it ended up being right through lunch. In the end, he said that, and the other guy with him said, “Don’t take that badly, Kevin. It’s a compliment, in a way.” At this point, I think I’m the de facto chairman of the asshole community, but I don’t consider myself an asshole. I just tell the truth, and some people don’t like it. I think that’s exactly what this character Milton was. I didn’t take offense at all. I was honored to be considered, and we went through quite a journey in sort of working on this script for that character.

Josh and Ronald have mentioned that they think through all sorts of details in the backstory of their characters. Did Milton have that? Were you privy to it?

I went online like everybody else could, and I saw the inspiration of who this guy was. Like everybody else, I’d seen Uncut Gems, and these two guys—I say this in a nice way—are pretty sick puppies. They write very twisted scripts. And this whole story is really about the birth of the American dream, in my view. If you think about the hustle and the optimism post-Second World War in New York, it really started there, this whole thing about entrepreneurship in America, the American dream. I feel like I’m an ambassador for it through Shark Tank, and I think that’s one of the reasons they said, “Let’s pull from that inspiration and make Milton Rockwell that guy.” I found that very simple to do because that’s who I am.

Were you encouraged to lean into persona you cultivated as a Shark Tank host, or were you trying to bring in more of the fictionalized character?

I’m not an actor, and I’d never done scripted before. In fact, the journey into this role is a little controversial. My agent, Jay Sures, called me and said, “Hey, this has come along. You’re not an actor. We represent you. We’ve built a pretty big franchise with you over the years, and I just have to be transparent with you as your friend and agent: We’re worried you’re going to shit the bed. That hurts business, and we should discuss this.” And I said, “Well, how do you know I’m going to shit the bed, Jay? And how do I know I’m going to shit the bed until I try this?” I’m very fortunate I don’t need more money. I need more time, and I want to spend my time doing absolutely extraordinary things. Why wouldn’t I try this? It’s certainly outside of my comfort zone, which actually gives me a lot of energy. I want to try and see if I can do it.

Josh and Ronnie never said to me, “You’ve got to take acting lessons.” In fact, I don’t know what the rules of acting are, and I don’t care. I’ve certainly never taken any lessons. I know how to do live television and reality television. I’m very comfortable getting in front of the camera, and I know how it works. What I was worried about was: When is the moment when I get on that set where I’m no longer conscious that I’m on a movie set and I’m in the room being Milton Rockwell? That was the only question I had, and I couldn’t practice for that.

he first day we shot was my longest scene, with Chalamet in the French bistro where I’m setting him up for understanding he’s going to lose, and that’s why I’m going to back him. But I was pleasantly surprised when we started filming [by how] meticulously created that environment [was]. The menus, the watches I was wearing, the pen I had, everything was from 1952. The way Chalamet works is he’s Timothée Chalamet until we’re about to start shooting. He stands up, walks around the table for 20 seconds, and comes back as Marty. I mean, a total transformation. I saw that happen once, and I got right in the groove.

On set, what kind of direction are you receiving from Josh? Could you feel his experience coaching performances out of first-time actors?

I don’t know if this is a trade secret, but I’ll tell you what happened. Ronnie’s in the production tent, and Josh is directing. They have an IFB between each other. Ronnie’s watching every single shot, and they keep doing it until they both think they’ve got the [take]. That may take five to 10 takes until the script piece is nailed, but then, we don’t stop. One or both of them may have caught a spark from a mistake or an improvisation during one of the takes, and they want to explore that. Then, we start doing a bunch of improv and riff on the idea together.

When I finally saw the film last night for the first time in its entirety, I realized that 50% of these scenes are improv. They took the kernel of the script, which I know well now, but there’d be a line in there that was completely improvised and came out perfectly. I would argue that his real talent is identifying while he’s shooting something he didn’t see and drawing it out of his performers. He says, “I want to go down this direction.”

And when you’re shooting [only using one camera], it’s a slow process, but look at what he got. It’s what he doesn’t tell you that is the magic. He doesn’t say a lot, but you’re just not done until you’re done. It’s not a democracy. I’ve never worked for anybody, so it was a bit of an adjustment, because I would say to him, “We’ve done it 15 times, I think we nailed that. We can move on now.” He just looked at me and said, “What the fuck are you talking about? That’s never going to be your decision. You’re going to keep doing until I say you can stop.” He only had to tell me that once, and I got the joke.

Whether it’s Marty in the film or some aspiring entrepreneur on Shark Tank, how do you separate the dreamers and the doers from the truly delusional?

These people practice a million times in front of a mirror, but they’ve never been out there with the lights and the cameras. Now, they are. They’ve got billions of dollars in front of them. They’ve been waiting their whole life to do this, and they can’t speak. I’m right in front of them, 12 feet away, and I just look at them. Not smiling, not frowning, not even blinking. I don’t say anything, and it’s very uncomfortable for them—for anybody, frankly—to have somebody just stare at you and not unlock their gaze. Within 30 seconds, maybe 40, I can tell without a single word being spoken, winner or loser. I lean over to Lori [Greiner] or Barbara [Corcoran] and say, “This is a loser.” And I’m never wrong. Now, why is that? Because if you can’t communicate who you are with your aura, your presence, your eyes, and your demeanor, you’re going to fail.

In life, people talk too much, and they don’t listen. The ratio is about 2/3 talking, 1/3 listening. That’s the average arrogant person. However, if you reverse that ratio, particularly in business, you will become very powerful. It worked for me recently in settling litigation, and this worked for me in the context of the film, but if you’re in a room negotiating something and don’t say anything for about 30 seconds, you’re going to find the other side starts talking. They cannot take the pressure. They’re squirming in the absence of interaction. And that’s incredibly powerful because they’ll blurt out something they shouldn’t have told you because they feel they have to. It’s a remarkable power, and I’ve built it into Milton. There are many moments of pregnant pauses. It’s a crazy, crazy thing, but it works. People just talk too much.

Do you see any of yourself in the character of Marty Mouser?

Yeah, I was Marty once! I don’t know if we got it in the film, but a lot of the improv said, “Look, kid, I was you. I know exactly how tough it is, but you must listen to what I say. If you want to be successful, you’ve got to serve.” In character, we started to be arrogant toward each other, which was wonderful. But he’s trying to prove he’s already made it to Milton’s status, and I’m constantly explaining to him he’s nothing but a cockroach. He’s an absolute nothingburger with zero power, and he is speaking to a master who could give him the path to success, but only if he does exactly what I say. The tone is that he just refuses to do it, and he should be punished for his insolence. That’s where we went with that.

Did you have any part in writing Rockwell’s final line about being a vampire since you joke about being one yourself?

We’re sitting around in the afternoon, and we’d started at 7:30 in the morning. I said to them, “Guys, as Milton, I’m extremely dissatisfied. I’m very unhappy because this little fucker has screwed me over, and he’s walking away scot free. It’s just not right.” I said to Ronnie, “The guy is winning the game in Tokyo, the exhibition match that I funded. He totally fucked me! You think I’m gonna let him get away with that? You think I’m gonna walk away? He destroyed everything I put to work there, and all the money I put into it, all for his ego even though they kicked him out of the finals. Everybody he touches, he turns to shit.” And I said, “Look, I’m a vampire. I was born in 1601. I gotta bite this guy’s neck. He’s got to live in misery in perpetuity.” And Ronnie said, “Oh, that’s sick.” And we went way down the road with that one. That’s how that got introduced. It’s a softer version of how dark we got, even for them.

I love the ending. I think it’s a form of redemption, but I still felt he didn’t pay enough. But that’s why these guys are great. When you’re actually shooting it, you’re so involved in the character that you help create little nuances. I’m not saying you rewrite the script, but the razor blade scene with Gwyneth, that was originally a Q-Tip. I was walking out saying, “Hey, did you use my Q-Tip?” She said, “You guys are all men. You don’t understand. She would have used the razor, made it dull, and the guy would have cut his face. That’s what women do. They’re lazy. They just steal the razor.” My wife wrote that. What’s important for the way those guys work is that you aren’t really acting. You’re in the moment and the scene.

You’ve said 30% of your day should be devoted to doing something outside your comfort zone. What did this film give you, whether or not you continue acting?

Well, number one is I’d like to think I didn’t shit the bed. Most of these sneak peek screenings that have happened over the last six weeks have been with industry people, and I’ve been offered two scripts now in two different directions. So I certainly know I’m not getting typecast, but I haven’t read them yet. I want to ride this for a while because this has been quite an experience, and it was very time-consuming. I’m glad I did it, but I just want to see what happens. I’ve asked my entire 11 million followers to give me their opinion of the movie when you go see it. We’re getting these positive reviews, but I want to hear what everybody thinks about it.

I found a few instances where you referred to Rockwell as the villain. Is that your take on the character, or was that also echoed by the filmmaking team?

No, Milton is a very complex guy. He’s not a villain. He’s in a loveless marriage, a marriage of convenience. His son was killed in the war that broke up his first marriage. He’s evidence that money does not buy happiness. I wouldn’t call him a happy guy. He’s a successful entrepreneur and continues to be, but he’s a tortured soul, so he’s also paying a price. Money can’t buy happiness, but it makes being miserable a lot easier. But that’s Milton’s story. He’s very wealthy, and he’s miserable. He’s getting along in his life, and he’s trying to deal with it. There might have been love between him and his wife at the beginning, but she’s also a broken woman trying this comeback. Everybody’s so fucked up! This is the hallmark of a Ronnie Bronstein/Josh Safdie script. It’s a sea of misery and unfulfillment, yet it has that moment of redemption in the end that’s so beautifully acted by Chalamet. I think he should have had two vampire holes in his neck for fucking up everybody’s life like that, but that is for the sequel.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.