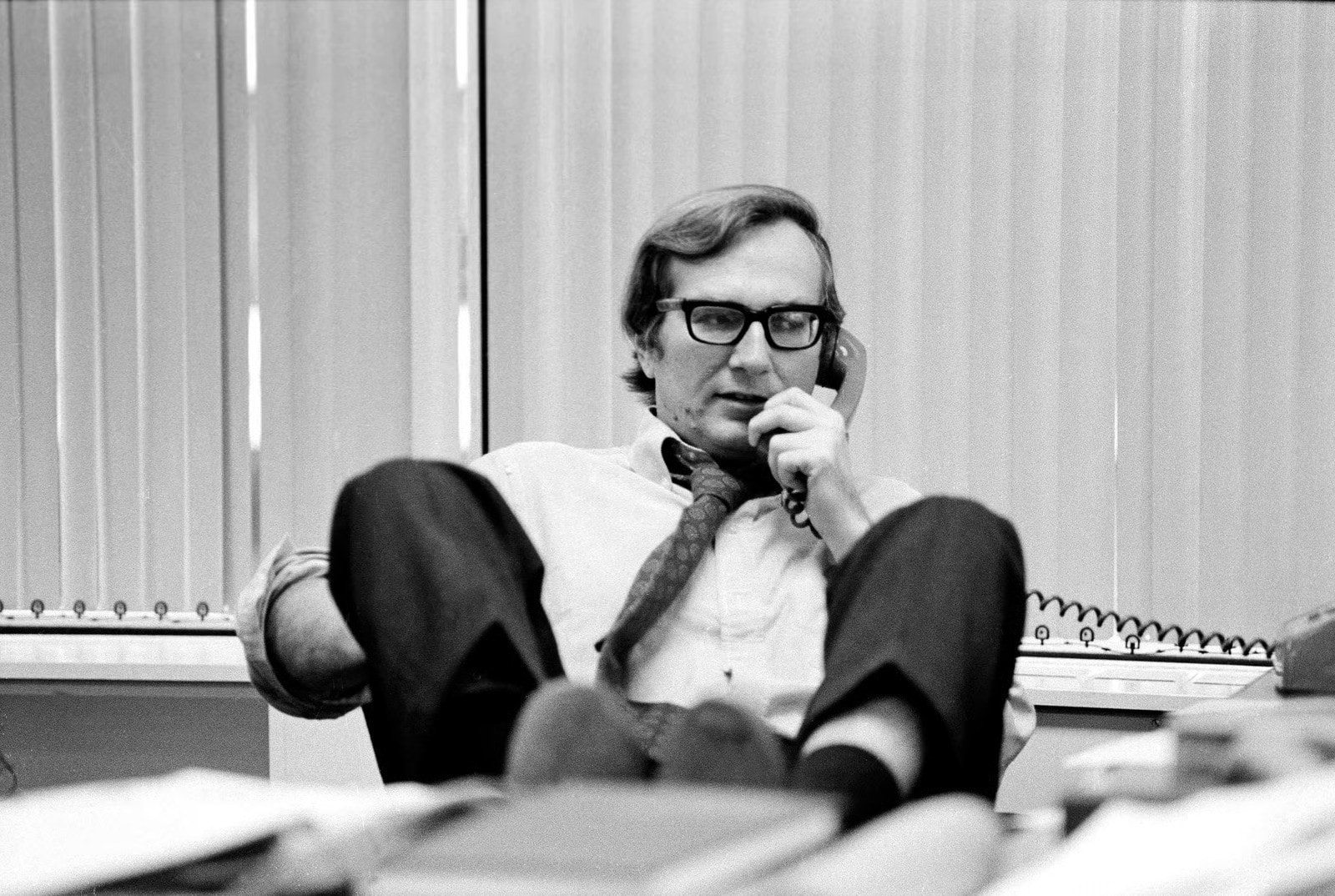

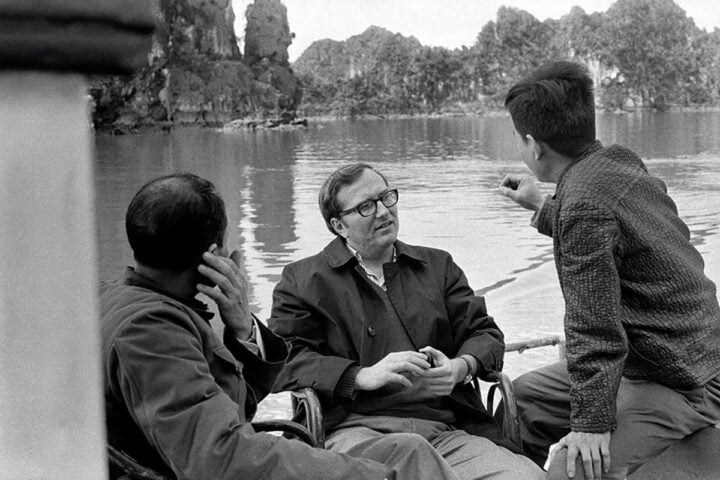

Legendary investigative journalist Sy Hersh, best-known for his reporting on the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War, resisted Laura Poitras’s entreaties to be the subject of a film since she first approached him in 2005. But Hersh finally relented and agreed to sit for interviews with Poitras alongside co-director Mark Obenhaus, a longtime collaborator who first worked with Hersh on a documentary in 1985.

The product of Hersh’s reluctantly offered openness is Cover-Up, an astonishing chronicle of the biggest stories of his over six-decade career. Poitras and Obenhaus unpack scoops from My Lai to Abu Ghraib and even contemporary reporting in Gaza in a largely chronological fashion, which allows the magnitude of Hersh’s contributions to the public’s understanding of institutional malfeasance to accumulate steadily. The subject’s colorful narration provides a propulsive backbone to guide viewers through the dark history he helped uncover.

Alongside each bombshell piece of reporting, the film opens a window into Hersh’s extensive and empirical journalistic process. “We are a culture of tremendous violence,” he observes to summarize his body of work. Poitras and Obenhaus’s searing documentary portrait of the man and the country he’s devoted his professional life to makes that conclusion difficult to refute.

I spoke with Poitras and Obenahus ahead of Cover-Up’s awards-qualifying theatrical release. Our conversation covered Hersh’s legacy, how their directing partnership came about, and what keeps them going in their own mission of holding power to account.

Removing it from just a single person who exemplifies it, like Sy Hersh, what’s great investigative journalism to you?

Laura Poitras: Everybody’s going to bring their unique skills and passion to what they do. I can speak about Sy, who has an amazing way with words. He’s hilarious. He’s a gossip, and I think he probably outsmarts a lot of people whom he talks to. And he’s just relentless. Even still, at 88, he puts us to shame in terms of his energy. He has a moral compass that just completely rejects lies and can follow his instincts. I think a skill he has is knowing where a story is.

Mark Obehhaus: It’s following an instinct. I think Sy probably had quite a number of tips coming his way in that period of time [when he broke the My Lai story]. But one of them made him go, “Hmm, maybe there’s something here.” It wasn’t a slam dunk. He didn’t really get a lot of information from the tipster. I know who it is, and [the source] didn’t know the whole story. He just heard about this thing. An investigative journalist has to have an instinct that guides them. I think you have to have a general skepticism about the official narrative, and Sy had that in spades in that period. I think there are still plenty of journalists who have that skepticism and doubt about the official narrative, whatever the subject may be. In the period of My Lai and the Vietnam War, as difficult as it was to get his story out, it was embraced by the gatekeepers and establishment once it was out. Now, I think it’s much harder to break through.

How did your directing partnership on Cover-Up come about?

LP: I’ve been stalking Sy for a while, since I made this film [My Country, My Country] in Iraq in 2005. After finishing All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, I was like, “Oh, it’s time to reach out to Sy again.” He was like, “Why don’t you talk to my friend, Mark?”

MO: Sy and I had been cooking up a film since about 2020 and were hoping to get into production. That was a film that only tangentially relates to this film, but it was going to be a personal profile where the action line was going to be his pursuing more reporting on My Lai. Believe it or not, there’s material that’s come out in the last couple of years that he had no idea about and is even more devastating in terms of the cover-up. It wasn’t really going that well, and I think Covid just destroyed the whole project.

We kept at it, and then Laura made her every-five-year request. It just happened to hit at a point when we were very actively talking. I thought that her film on Nan Goldin was wonderful and was in the form that I had in mind for any film we were going to make with Sy, and it was just a perfect fit. Maybe there was a little skepticism that it would work out on Sy’s part. But Laura and I met, and thought that probably our best chance of getting this made was to collaborate.

LP: Mark understood something about how my work could cover many decades with a central protagonist. In the conversation, he also said, “My stepdaughter, Mia Cioffi Henry, is a cinematographer.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” She’s somebody whose work I’ve loved and admired for a really long time, and Mia also knew Sy. He had followed my work over the years, particularly the work around the National Security Agency and Edward Snowden. All those things built enough trust for us to invade his office.

Before I agreed to fully commit and raise money, we did a proof of concept. We brought on Olivia Streisand, one of the producers of the film, for the archival research to pull what she could find. We spent three months cutting to set some aesthetic rules, to see what the archival was like, to test the relationship between Mark and me, and then to do some initial interviews with Sy. Those interviews didn’t make the final film, but I think we created a template.

How do you balance the portraiture of your subject with the stories he covers and what they reveal about society?

LP: After you work for a while, you start to see patterns that maybe you didn’t recognize in the beginning. I’ve been doing a similar type of portrait of an individual, but also a critical lens on the larger society. It’s territory that I know, and I like it for a number of reasons. I like making portraits of people, and I consider this a portrait, but it’s also very much a history of the United States. At least from the conceptual level, it felt like they were always together. But the balance is tricky because you don’t want to go too far in one direction, into a history lesson or into a biopic. I’m very allergic to biopics. What’s the through line? There’s a lot of biographical detail that’s not in the film, but we included things we felt informed what motivates him as a journalist.

Why was it important to capture this in a feature and not make it episodic?

LP: I was really interested in drawing connections across time and looking at patterns and cycles. Yes, we go into specifics about different eras like the My Lai reporting or Abu Ghraib, but I was interested in how they resonate and speak to each other. By putting them in a single film, you see how these cycles repeat. If it were episodic, you would feel like you were marching through history. One of the things I really wanted to avoid is the audience thinking that history is inevitable. History is alive, and it’s being made now. To juxtapose these many different historical moments then allows us to talk about themes of impunity and violence in this country that I think would get lost if we did it episodically.

How did you come to structure the film using My Lai as narrative bookends?

MO: It was always going to be a film that had two threads. One would be active, present-tense reporting. In this film, the active reportorial line is Gaza. It crops up here and there. You see him as a contemporary actor dealing with Gaza as well as in the historical realm.

At one point, I thought we should start with Abu Ghraib because it’s much more contemporary, but My Lai is really the foundational story for Sy Hersh. It’ll be on his tombstone, and I don’t think we would be making this film had he not exposed My Lai. It was a huge historical and journalistic event that had a profound impact on the national attitude toward the war.

There are very few stories that journalists can claim have really changed the course of history. The My Lai story, together with the Pentagon Papers, was a one-two punch that really brought the American public around to profound skepticism about the war. Embedded in the story are all the themes of skepticism about power and the attempts by various branches of government to cover up their misdeeds that resonate to this day.

One of the reasons that the ending of Calley [the American lieutenant court-martialed for his participation in the My Lai massacre] works so well is that we’re in an environment now where perpetrators of crimes are being pardoned, the press is being suppressed, and sources are being intimidated. There’s a moment that the Calley story gives us at the end, when you realize that oftentimes the perpetrators of the stories Sy has reported on are let off by the powers that be. I think that’s happening right now as we speak, and it has a real resonance in contemporary life.

Thinking about how the public took up Calley’s story and took his criminality like a badge of honor was startling. It’s scary to live in a time when investigative journalism can put the truth out there, but the public can say they either don’t want to hear it or care.

MO: I couldn’t say that better than you’ve just said it. That’s the real disturbing reality of that episode, and it’s very relevant today. The actual events around Calley are a little bit more nuanced, but the story is that he was exonerated, in a sense, and got away with it. A portion of the public was divided about such a heinous event as the My Lai massacre, which speaks to our contemporary situation, where there’s controversy over all kinds of things. Look at the boats being blown up right now. I don’t pretend to know all the facts of that, but you have a divided public about that. Everything now is divided, and Calley was emblematic of that story.

Laura, seeing as you’ve made several documentaries with a similar structure, are you any more enlightened as to why the U.S. is caught in a cycle of violence and criminality with so few consequences?

LP: In this country, it comes down to impunity. Catastrophic events and atrocities are committed, and the people responsible walk away without any punishment. This happens over and over, and it sets the stage for it to happen again. That’s the total motivating drive of this film, why we’re covering these cycles and what they say about this country. I also think we have a problem in this country about how we don’t deal with our past. It’s like we have amnesia and forget about it. A filmmaker friend who I have deep respect for, Raoul Peck, looked at the film and said, “You know this country is based on cover-ups, right? You have the genocide of the indigenous people through to slavery.” These are the great cover-ups of this country that we don’t deal with. And if you don’t deal with them, then you set the stage for them to be repeated.

I loved the emphasis given to the archive, from the way you framed the interviews in front of Sy’s boxes to the photography of the notebooks themselves. How did that emerge as such a visual focus?

LP: I was obsessed with his yellow notepads from the first time I met him in 2005 and going to his office. You just realize how much history is there in these gravity-defying stacks. When we started working, I felt the yellow notepads would be a very material way to travel through time. You could turn a page and go from the 1970s to a different time, and they would have that materiality. Originally, I was hoping that we could always have notepads, filming from below while interviewing Sy. But that got a little cumbersome, so we ended up filming them on a separate light stand and brought Sy to them, and he would walk us through the notes.

How were you balancing bringing in some of the voices in Sy’s orbit to break up what might otherwise just be a monologue?

LP: We had a rule in the shooting that the person had to have direct knowledge of the reporting that was being discussed. Amy Davidson Sorkin was Sy’s editor at The New Yorker for Abu Ghraib, so she got the phone call when he got the Taguba Report [the Army’s findings of the prisoner abuse in the Iraqi prison]. We’re using the documents a bit like evidence, and we wanted eyewitnesses who could corroborate and tell us certain things about what it is like to be Sy’s editor or source. There were some more global themes we were interested in, but they had to be people who had direct engagement with the reporting. So that was the rule.

What do you make of Sy being on Substack? Are we to think of it as more empowering that a journalist now has tools to operate independently, or indicting that our corporate-owned media is too scared of the big stories?

MO: I think it’s both. I suppose the jury’s still out on Substack, but it’s quite a wonderful venue for someone like Sy to report, express opinions, and have a following, particularly for reporters who are no longer with the few establishment organs that exist now. It’s a good place for Sy. To me, it references his early beginnings with Dispatch News Services, this renegade outfit that put the My Lai story into the public consciousness. That said, I’m just very concerned that there isn’t a way for reporters to break through in a big way. There’s such skepticism about news and truth, and it’s a very different environment today. I think Sy’s comfortable on Substack, but I wish that the venue were broader and recognized as more authoritative.

LP: Sy always had a bit of an outsider, punk [attitude] toward his bosses, so it’s not a surprise. We’ve seen more and more journalists turn [to Substack], partly because I think that legacy media has failed many journalists. But I don’t think it’s a solution. Sy’s best reporting is really hard to do. It requires enormous amounts of time and resources, and we’re in an era where news-gathering institutions are less and less inclined to want to take risks. That’s really scary.

I’ll close by asking you the same question posed to Sy: Why do you keep doing it?

MO: Like Sy, I think that we hope to break through with the ideas and values represented by the film and resonate with people. One of the things that I’m very grateful for is that this film has been embraced by Netflix, which has a huge audience base. They’ve been extremely supportive of this. You make these films because you want people to see them, and you want the films to make a difference. The venue is incredibly important.

LP: Sy’s answer resonates with me. We can’t not respond. He’s talking to a source at one point about how we can’t give in to the politics of despair. We have to keep doing it, even though we might feel like it doesn’t make a difference. Things do change. There are tipping points, and you have to keep doing the work. He says, “You can’t have a country that does that and looks the other way.” I agree. You can’t look the other way.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.